I grew up in England in the post World War II era of rationing, a time of general shabbiness and of the food that in my view was a force in creating what had been the largest Empire in the world – adventurers fleeing mother’s home cooking. As for tea, it bore no resemblance to today’s brand images of Imported From England heritage: cucumber sannies, Earl Whosit, and oollygongs or whatever that Chinese stuff is called. I do not recall even hearing of the existence of green tea.

Tea was just “tea”: black, dark, sugar-laden, and never, ever associated with words like delicate, floral or tippy. It was brewed in metal and china pots left unscrubbed and tannin-layered. The cliche of the 1950s was that you should have enough sugar for a spoon to stand upright in the brew. That American invention of 1908, the tea bag, failed to cross the stormy Atlantic until 1953. When I left England in 1967, only around 3% of teas were this dust in a paper pouch. I’d never encountered an Earl Grey, which my US hosts so generously pushed on me as “your favorite English tea.” Not mine, then or now.

There was one special haven of tea, perhaps even more central to everyday English life than Starbucks has been in the US. This was J. Lyons, whose tea houses from the 1890s through to the early 1980s offered the best and most affordable quality, service and ambience. In addition, a fact that is almost unknown to Silicon Valley, Lyons invented the business computer, in 1951. Its Lyons Electronic Office made it the very first company in the world to design, build and implement a general-purpose computer that was used in order processing, inventory management, forecasting, and payroll. LEO was the base for the entire UK computer industry that for a brief period led the world. Now, the hi-tech company that a tea house founded is long lost as part of Fujitsu. Lyons’ tea, biscuit, bed and breakfast pre-motels, and hotel businesses were sold off in the 1980s.

[bctt tweet=”The cliche of the 1950s was that you should have enough sugar for a spoon to stand upright in the brew. “]

Lyons tea shops were distinctive. First – anticipating Starbucks – they focused on ambience, with a fresh interior design and waitress service, not at all typical of what was in essence a fast food “caff.” They were built on the working class traditions of tea, not the aristocratic ones. Tea really did bind the culture together. In World War II, it stood for the sharing and welcoming unities of the community. This photo from an underground bomb shelter in London is not an artificial element of nostalgia but memory. And, yes, the teapots were like that.

Lyons was part of the democratization of tea, led by a few Sam Waltonesque titans like Thomas Lipton and the Tetley brothers. The drivers were reliability of supply and quality, affordability and a brisk, fresh taste. Lyons focused on food production: “sweets” – all the jam rolls, custards, biscuits and ice cream, which is the real roots of the tourist image of tea as being accompanied by elegant strawberry scones and clotted cream. Uh, no. Bikkies and sugar, milk and no fresh fruit in sight; that would overpower even the most stewed Ceylon broadleaf.

[bctt tweet=”Tea really did bind the culture together. In World War II, it stood for the sharing and welcoming unities of the community.”]

Lyons was, before we used the term, integrating the supply chain. It imported its tea via the London docks and had a sophisticated blending lab from which it shipped a million pounds of tea a week to 200,000 outlets. The tea houses were their brand. They were comfortable and inviting. You never felt awkward, the way you would have been overawed and intimidated by the type of hotel that served up high tea. English tea as a drink was built around low breakfast, that wonderful meal of bacon, eggs, fried bread (yes, in lard), tomatoes, beans, toast, sausages – the famous “bangers” of unknown origin and unstated ingredients. English Breakfast – or, as we Brits called it, Tea, was strong enough to stand up to all this artery-hardening diet. The idea of a green tea or light oolong belongs in a parallel universe.

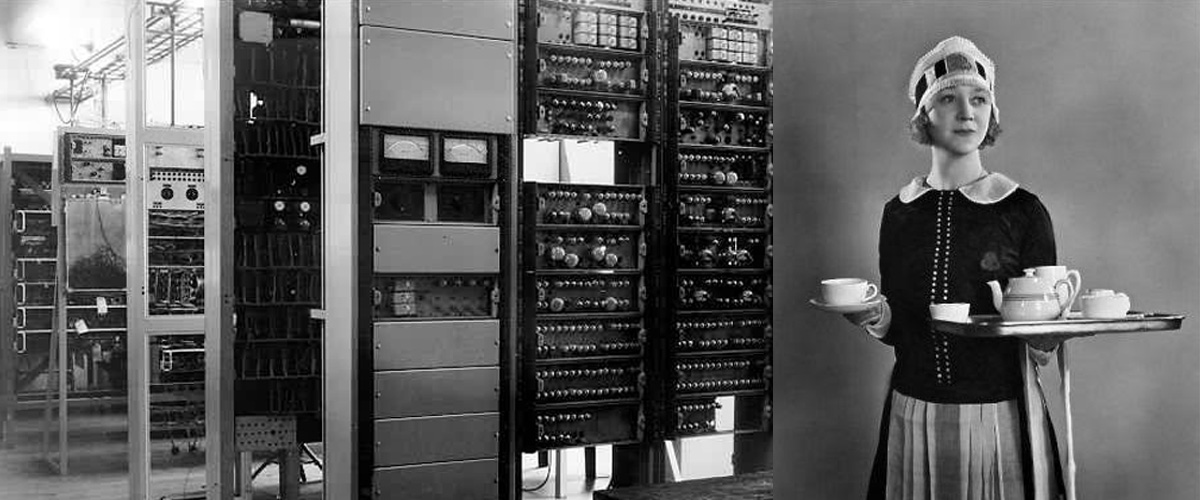

The waitresses were professionalized and called “Nippies.” They were all dressed up in a crisp formal black and white outfit that now seems straight out of Downton Abbey. Note the big cups and metal pots; you drank tea not sipped it. Lyons Corner Houses were the epitome of English nosh. The tea was the draw and it was always fresh, strong and flowing. You ordered by the pot and drank by the bucket not the thimble.

This was a well-managed firm. Its senior executives spotted earlier than any the opportunities of the computer just developed in the US, the famous EDVAC in the late 1940s. That was a machine for calculating and had just one input and one output channel. LEO was in full operational use in 1951. It could handle scanning, card and tape reading, automatic data validation plus a variety of printers. It ran up to twelve concurrent applications. Its 64 mercury tubes had 2K of memory each; a tube was five feet long and weighed half a ton. LEO occupied nearly five hundred square meters. Its first instruction sets took 1.5 milliseconds to perform. One later feature of the LEO III was a loudspeaker that broadcast a tone that operators could listen to and detect if a program was stuck or looping. Lyons pioneered outsourcing and handled all the phone bills for British Telecom as late as 1981. Underinvestment and the onslaught of IBM eventually killed off the firm that acquired and built on LEO.

It was a product of genius. One commentator on the celebration of its sixtieth anniversary noted that it was as if Pizza Hut developed the PC and McDonalds invented the Internet.

Lyons faded rather than failed. It was spread very thin and changing demographics, the tight government constraints on financial capital, and selling off of business units eroded growth. Dominance in the tea industry passed from outlets – tea shops and houses – to the packagers and retail brands.

Now, fifty years on, I drink a wide range of really good teas, some expensive and many not. I don’t have any nostalgia for the brews of my English heritage. But what stays with me from Lyons is how much tea is part of our memory because of its ordinariness. Lyons was a treat but a very comfortable and relaxing one. I think tea lovers all have some internalized “anchor” taste: the type of tea of pleasant memory. What’s your own anchor? Are you treating it well and exploring new varieties that enhance it? Are you choosing your tea to be special as part of your day and not just for special occasions?

What tea is all about is captured in my Lyon’s recollections: making the routines of the day more comfortable. That applies not just to favorite lower end brews but to the showcase ones, to the decent Nilgiri and Keemum to the first flush Castleton and Mao Feng: the pleasure of comfort in the routines of everyday, to be stored in the memories of yesteryear.

A final piece of trivia about Lyons. One of its employees was a young chemist, Margaret Roberts, assigned to develop emulsifiers to preserve the fresh ness of ice cream. (She had been rejected by the first firm she applied to as “headstrong, obstinate and dangerously self-opinionated.”) You may have heard of her by her married name of Maggie Thatcher.

Nippies, LEO and the Iron Lady – quite a history.

6 Comments

Greta memories. How you could have lost any nostalgia for what passes for modern tea is beyond me. The modern stuff is tea by name only and not by taste.

I think we share the same view. I haven’t had a bad cup of tea in over a decade — I drink only”nonmodern” tea — no tea bags, blends or flavor-enhanced stuff. I go for whole leaf artisan teas, with a credible pedigree. Once in a while I will sip at a bag/blend tea for my research and writing but it is awful. I hope in my blogs and books to help people find good basic teas at a decent price; the main blocks are that they are tend to be unfamiliar with what’s out there and take the packagers/brands’ marketing hype as fact not Hallmark card poetry.

In the past few years, I have found that for any Agribusiness mass market tea I can find an Artisan one at the same cost that is better in every way. I wish I was smarter at knowing how to spot the growing frauds — the Jasmine Greens with extra chemical shine and the mixing in of lower grades to a mid-range White Peony and Tie Guan Yi but there is no way I can even finish a “safe” Earl Grey and those appalling greens.

A wonderful essay – fascinating.

Thank you,

Thank you so much, Mary.

Never boring, always incite-full.

Pingback: Tigers and Tea - Tea Stories - Still Steeping: Teabox Blog