Around the time I hit middle school, I began helping my mom in the kitchen. One of the very first things she taught me was how to make a cup of chai and it instantly became one of my favorite things to do. I’d stand on a short stool to reach the counter and my mom would give me tasks, to pass the can of sugar or stir the chai as it simmered, while she’d act the role of a potion master, craftily combining one part water, two parts milk, a heap of tea leaves and just one short spoon of sugar. If it was raining outside or was particularly nippy, she’d toss in a few whole spices – anything she could reach in her spice box, cardamom, cinnamon, clove, fennel… Ginger occasionally found it’s way in, especially when somebody in the family was under the weather. When it was ready, we’d drink our chais in big ceramic mugs, with a side of Glucose biscuits, a light sandwich or a snack with a similar disposition.

This is chai as I have always known it.

Unfortunately, chai plays in the little league in the larger world of tea. Many still believe that any black tea consumed with milk and sugar qualifies to be a chai This notion of chai is not only bad but wrong: excessively simple and lessening.

A good, authentic cup of chai, those you’d find at most homes in India and its street corners, is a perfect balance between tea and milk. You do not steep chai, you brew it. You brew it in way that perfectly combines the tannic strength of the black tea with sweetness of piping hot milk, embellished further by the addition of sugar. It’s a perfect drink, in its own right. But no tea expert will ever tell you that.

For purists, just the idea of drowning tea in milk is blasphemous; they think of it as something that diminishes the tea’s personality, which is perhaps why they never encourage it in their dialects. Chai lovers, on the other hand, view the drink with a lot more enthusiasm. It’s not just the chemistry of flavors which works for them but the emotional spaces to which it lends itself so effortlessly. Chai is a welcoming sight, much like the sound of crackling wood on a winter evening or freshly buttered toast first thing in the morning. It’s the kind of tea you’d lay out for your friends and family when they are over because everybody loves a sweet treat. It’s nourishing in every season. And if it’s the thing you grew up on, nothing else can comfort you better.

[bctt tweet=”You do not steep chai, you brew it.”]

Chai is native to India. No historical account exists to vouch for this but given how (now) over six generations have grown up drinking chai in one form or the other, it wouldn’t be an incorrect claim. Sometime in the first half of the 20th century, the Tea Board of India, in an effort to boost consumption of tea within the country, decided to run a slew of advertising campaigns that built tea into people’s routines. What they were promoting was, in fact, a lower grade tea, most likely fannings and dust, which is a residual-class of tea obtained after the leaves have been processed for their better part. The flavors of this tea were so strong and dark that a generous splash of milk and a wad of sugar was essential to counter its potency.

Much later in the 60s, when the CTC machines were invented, better quality leaves could be fed into this industrial-looking contraption that churned out, on a very large scale at that, even nuggets of black tea.

The vast majority took to it quite agreeably. Loose-leaf teas were so expensive that they could never take off commercially within the country, but CTC granules of lower grade leaf were far more susceptible to go mass. And it did. The addition of milk and sugar remained.

With time, consumption of chai went from being a social ritual to a functional one, built intrinsically into the daily life of the common man.

It may have had humble beginnings but chai is conditioned into my system now. And much the same way it has grown into the very ebbs of Indian sociability and that’s just how it will be. It will never be an alternative to loose-leaf tea, nor should it. It may not match the aesthetic values of terroir, seasonality or make, but it reflects a highly enthusiastic side of tea you won’t come across in any other kind.

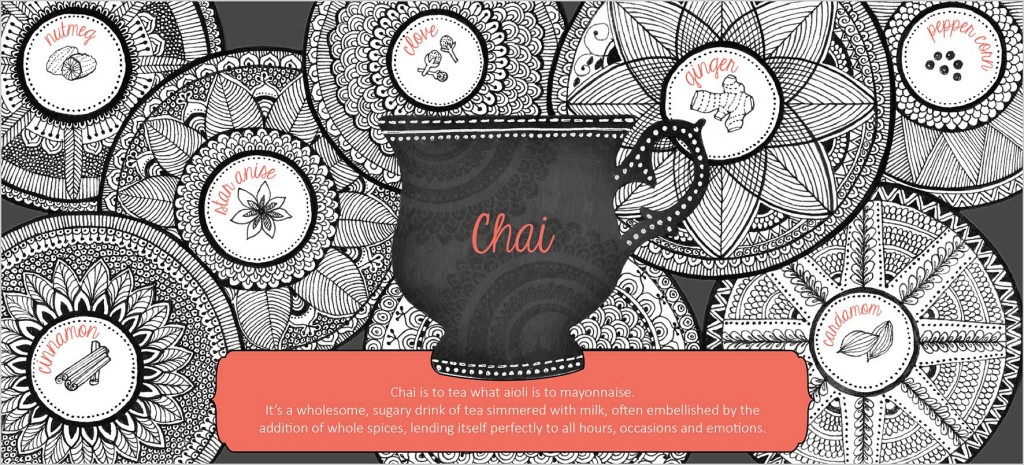

Illustration by Handmade by Radhika

6 Comments

Is the milk added after or is it boiled with the tea leaves? I have been searching for a good chai recipe for years. Still haven’t quite gotten the hang of it.

Hi David. The milk-first-or-not conundrum is something I have battled with myself. In my experience, I have found it is better to add milk later (once the leaves have had time to simmer and roll around in water) because this way you can control how “milky” or strong you want the chai to be. Adding milk first impacts the balance, and in trying to fix this by adding more water/milk, I end up with a little too much chai and not a good one at that.

Here’s a simple chai recipe you may try (makes 1 big hearty cup, about 150ml):

To about 3/4 cup of water add a full tsp of CTC leaves (you may opt for a strong, full-bodied Assam loose-leaf tea as well).

Put it to boil, and let the leaves play around in the now-dark brown liquor for good 2 minutes.

I prefer adding about half a cup of milk to this now-brown concoction. I use full-fat milk or milk with 3.25% milk fat (M.F.), mainly for its body/density. This makes the chai so much more creamier and tastier than a fat-free/skimmed milk.

Toss in sugar as per your liking.

Simmer for about another 2 minutes (let the chai come to a boil again, and once again after that…till it looks like toffee, well, almost)

If you prefer adding spices to the chai, toss in 2 decorticated cardamom pods/half a tsp fresh ginger/an inch of cinnamon stick to the brown liquor (before the addition of milk, i.e). During summers, you may try using lemongrass, fennel and mint as well (that’s my favorite kind).

Hope this helps.

Cheers

Thanks! I’ll give it a try!

Spicy ginger Chaiiiii…, the best Indian Chai.

Hi,

Which tea is best suited for chai (if we are trying to maintain both the aroma and the taste)

To make chai you need a strong, kick-you-in-the-face kinda strong black tea. Typically lowland teas (those grown in tropical conditions, nearer to sea level) are perfect for chai since they have a very dark, brisk and robust flavor profile. Look for a full-bodied Assam black tea – loose-leaf or CTC grain, for an authentic chai experience.