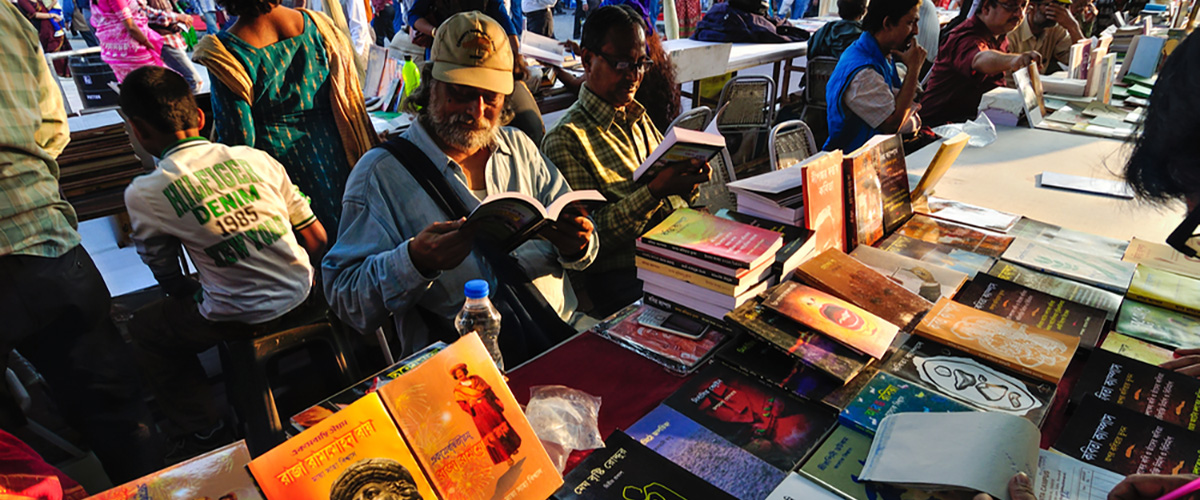

Here I am at last! I almost yell it out as I step through the metal detectors onto the sprawling fair grounds on Kolkata’s eastern outskirts, thrilled to be at the fabled book fair. According to legend, a bunch of enthusiastic young publishers dreamt it up in the mid-1970s at the old Coffee House in College Street. It has kept growing since, and is now said to be one of the largest literature events in the world.

To my right, are four big halls crammed with the stalls of publishers and bookshops, to my left a stage for literary and musical programs, and in between a vast area of pavilions representing museums, foreign countries, cultural and religious organizations, and the many snack stalls that the fair is so famous for.

Recently, taking the cue from the rising popularity of Indian litfests, the eleven-day-long fair added a three-day literature festival – turning the old book fair into one of the youngest litfests in the country. This year I get the opportunity to listen to authors such as Ashok Vajpeyi, P Sivakami, Kunal Basu, and one of my favourite travel writers Bishwanath Ghosh. Plus I am supposed to be onstage myself, participating in a panel talk. These talks are held in a tent in a corner and don’t attract the huge crowds who go about their book shopping, so the vibe is rather intimate, but when popular author Durjoy Datta takes to the stage the tent is suddenly packed with screaming youngsters.

In between sessions, I sip tea and stroll around the Milan Mela grounds, located just off the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass where the fair nowadays has a permanent purpose-built home. The event was traditionally held in the centre of Kolkata on the vast Maidan, but complaints from environmentalists combined with the traffic jams caused, forced it to relocate about a decade ago. Also, some years before that, when the deconstructionist thinker Jacques Derrida was the inaugural speaker, the fair caught fire and books worth millions were destroyed. Kolkatans joked about the “deconstruction” and quick “reconstruction” of the fair, but the fact remains that the new location is perhaps safer for a mega-event of this type. Here, the eateries and tea stalls are mainly concentrated to a separate food court so the chance that some vat of deep-frying oil will start a fire is slimmer.

There were apprehensions that people will not bother to follow the fair to its new location, but it seems the audience has actually increased. One of the organizers informs me that some two million visitors attend the fair, pointing out the long lines entering through the gates with empty bags while another queue is moving in the opposite direction, their bags loaded.

Mahesh Golani is a member of the booksellers’ guild running the fair and he tells me a story about a fellow who kept coming to his stall to browse a glossy book on the sculptor Michelangelo, priced at ₹8000. The staff thought he might be a thief, since he looked scruffy with his old dhoti and unshaven face. On the last day of the fair, however, the man returned with a bag full of five and ten rupee notes which took an hour to count – the exact price of the costly book. It turned out he was a poor farmer who had been saving to buy such a book for three years because he had always dreamt of being a sculptor. Humbled, Golani offered him a fifteen percent discount.

However, the book fair isn’t only about literature. Many of Kolkata’s most interesting restaurants open stalls to cater to the festival-goers. There’s sinfully deep-fried prawn pakoras, a Benfish stall with many varieties of fishy snacks, quail biriyani, Kolkata’s iconic kathi rolls, Tibetan momos, street food such as puchkas, Haldiram’s savouries, Bengali sweetmeats and of course tea, the local beverage of choice.

As I stand there with a roll sticking out of my mouth, an elderly bespectacled Bengali gentleman jumps me, clad in a freshly ironed kurta, and offers me an almost toothless smile. He insists that I must be Goldie Hawn. I point out a flaw in his logic – I am a middle-aged man, hardly an American comedy actress from the 1970s. Unfortunately, he doesn’t understand English but whips out an autograph book and requests that I sign it. He is so thrilled, as it isn’t every day that you get Goldie Hawn’s autograph in Kolkata.

I oblige. I am after all visiting the fair as a speaker and had hoped to autograph some copies of my own books. But they’re not yet widely read in Bengali, so at some level it vindicates me to borrow one of Ms. Hawn’s fans. She did some great acting in The Sugarland Express, Steven Spielberg’s debut movie from 1974, and I make a mental note to perhaps buy myself a blond wig.

Also, the booksellers’ guild gifted me a pretty Kali idol and about a kg of Darjeeling and Assam teas. Tea and books go well together. The tea came in handy and kept me awake through the many literature festivals I had to go to, because this winter I’ve been bingeing on book talks – I visited about ten of the best litfests that India has to offer from south to north. I was invited to several more, but had to say no due to dates colliding. This may seem like a lot of tea and literature consumed, but considering that India annually hosts more than a hundred litfests, I barely scraped the surface.

A hundred literature festivals in one single country must count as a world record! A decade ago there were very few, but all south Indian states nowadays boast of more than one litfest each. Chennai has not only a couple of general litfests but also hosts a quirky poetry festival which has included readings in tea shops and boutique stores. Want a book and a beach? Try the Goa Arts and Literature Festival. Mumbai has four festivals, including the streetsy one that is part of the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival where literature, street art, food and shopping go together. Apart from its general book fairs, New Delhi hosts the annual Crime Writing Festival which celebrates genre fiction by bringing together local and international thriller writers. If you’re looking for a more picturesque place in which to enjoy book talks, there are litfests in the hills – Jammu, Kumaon, Mussoorie and Shillong. In Assam, there’s not only a lot of tea but a translation festival. Or if your interest is literary criticism, try Chandigarh Literature Festival where critics elect the writers they want to be in in-depth conversation with regarding their books. Most of the festivals are either free or charge a very nominal entry, and in some cases they throw in free chai for the general visitors too.

One fellow novelist I met at a literature festival complained, only half in jest, that he had barely time to launder his underwear during the hectic festival season. He suffered from severe festival fatigue. Increasingly, whether one has a new book out or not, as an author one is expected to participate in the grand literary tamashas.

This trend was kicked off by the unprecedented success of the Jaipur Literature Festival. In its first edition, nine years ago, the Jaipur litfest apparently attracted a handful of visitors. This year the number of footfalls at Diggi Palace, where the festival is held over five days every January, is said to have been somewhere around 330,000 and the popular festival has spawned smaller editions of itself in the UK and the US. So just before going to Kolkata, I went to Jaipur, to enjoy the festival which brings together the biggest contingent of writers from India and abroad, including Nobel, Pulitzer and Booker winners, so much so that it has been given the moniker “the Woodstock of literature”. It is also the best curated festival – programs run on time and are moderated by hosts who have (mostly) read up on their subjects. Another charming feature of the Jaipur Literature Festivals are the turbaned chaiwallahs who serve a special ‘Diggipuri masala chai’ in clay cups.

The festival has a growing fan following. I met one dude who air-dashed from Bengaluru to Jaipur just to listen to his favourite author (who was making a rare appearance) and, a few hours later, air-dashed back to work again. At Jaipur’s railway station at night, students who travelled in from all over India to partake in the free festival but couldn’t afford to pay for hotel rooms, bedded down on the railway platforms to sleep.

Something about literature festivals seems to bring out the most extreme fanaticism in us book lovers. I too had my fan boy moment in Jaipur when I happened to walk past Alexander McCall Smith, and said hello to him, only to end up having a long chat, over cups of tea, on detective fiction in India which he was very curious about. In short, the literature festivals serve as a bridge, a wide and open one that crosses the gap between readers and their favourite authors.

If you bump into an author in the queue to the chai stall – which is rather likely at a star-studded event like Jaipur’s litfest – but can’t remember exactly what book he or she is famous for, the phrase that always works is: “Loved your latest.” Every author would like to believe that their latest book is their best! And if that doesn’t cut the ice, then you can just pretend that he or she is Goldie Hawn.

The featured banner shows the Kolkata Book Fair. Photo credit Rudra Narayan Mitra / Shutterstock.com