These gentlemen are on their way to afternoon tea.

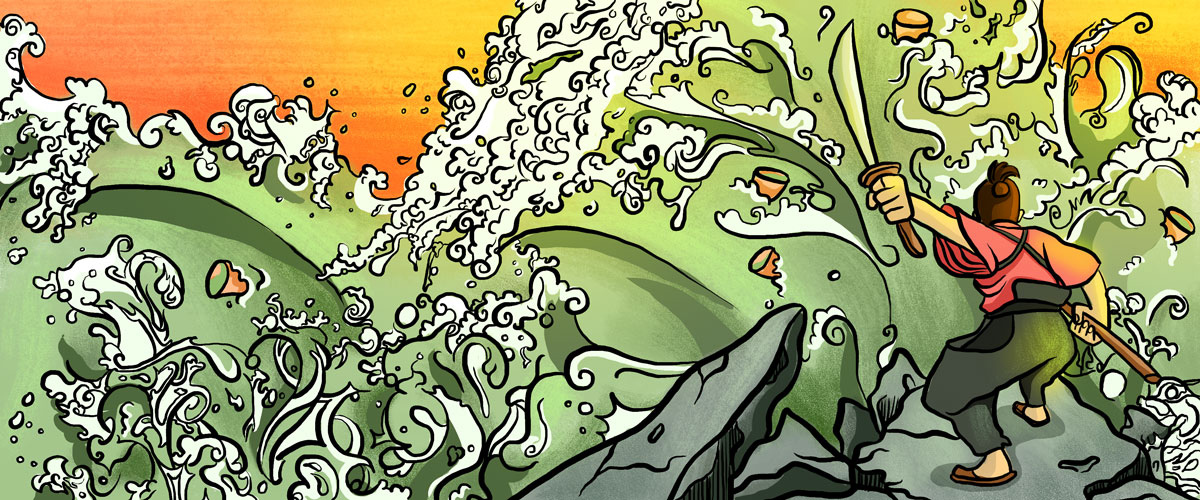

They are samurai. Their armor, swords and fearsome helmets are legendary. So, too, is the centrality of the tea ceremony in the Samurai Way. An obituary of a famous general speaks in awe of his more than two hundred beheadings in a battle. It adds that he was also a great tea master.

It may seem incongruous that the most feared warriors since the Viking berserkers were the main proselytizers, developers and practitioners of the tea ceremony. It reflected their very identity that was built on Zen Buddhism: discipline, ritual, purification and selflessness. The samurai were terrifying. And they were cultured.

These two facets came together during the rule of Hideyoshi, around 1590, the middle of the three great Unifiers who ended the incessant and destructive civil wars of Japan.

He launched the largest military conflict before World War I, invading Korea and then taking on the might of the giant Chinese Ming Empire. (This ended in a sort of tie.) He rigidified the social structures of Japan for 300 years by allowing only the samurai to carry arms (judo emerged as the peasant class only mode of self-protection) and also banned the “wandering” samurai who were mercenaries for sale. They were now tied to a lord for life. This system lasted till 1868, when the samurai were decommissioned. Around 20% were female and many came from the same peasant stock as Hideoyoshi. He aimed at creating a warrior aristocracy.

He built a close relationship with one of the great tea masters of Japan who raised the informal tea ceremony to an art form. It had evolved as a social forum for the nobility. Master Rikyu eliminated the class boundaries and added hundreds of steps and details, right down to hand movements, entry to the rooms of the special tea house, sipping, and sitting. He built portable tea houses that moved with the ruler’s court.

The tea ceremony became a mark of the samurais’ special status and Hideyoshi’s patronage. There’s some evidence that it was also integral to their training, sharpening their acuity, focusing their concentration and patience. This prepared them for the explosive violence they could unleash.

The tea was as distinctive as the ceremony: matcha, a powder made from deveined leaves from shade-grown bushes. The plants are covered with blankets for three weeks before harvesting to block sunlight and increase chlorophyll. The leaf is slowly ground by stone mills; it may take an hour to produce a single ounce.

Whisking and brewing demand exact and expert handling. A few too many grams, seconds and degrees produce a truly awful, bitter foamed sludge. Well made from ceremonial (versus culinary) grade leaf, it is a subtle, grassy and slightly sweet tea that lingers on the palate – and priced accordingly.

The samurai are gone. The ceremony is mainly for tourists. The matcha remains – and is timeless.

Featured illustration by Tasneem Amiruddin