Prashant Gurung’s dream, I thought, was as modest as his means: the waiter at the guesthouse of a tea garden in the Darjeeling hills wanted his eight-year-old son to complete school.

To me, that was hardly headline news. It is not uncommon for the underprivileged in India to give their children an education, however humble. The small town rickshaw-puller’s son who made it to IIT – India’s answer to MIT; the housemaid’s daughter who cleared the entrance tests for medical studies, the roadside fruit seller’s son who topped the school-leaving exams…. I mean, the papers are replete with such stories.

And let us not forget, India’s Prime Minister was once a “tea boy” at a roadside stall.

So when Gurung proudly told me of his son going to school, I smiled and uttered some inanity like, “a good education is essential etc…”

Moments later, I realized I had misread him; the man who waits on guests like me at Namring tea estate is talking of an “English-medium” school for his son, and not a charitable one either.

Now, that is something not often seen – India’s underprivileged sending their children to a school where the medium of instruction is English, a category of institutions that is usually associated with the privileged, unless it is specifically run for the poor.

[bctt tweet=”There is a cultural change happening in the gardens in Darjeeling. There is 100 per cent literacy in the gardens. This wasn’t the case earlier.”]

I quizzed Gurung on the new fees and his pay, and realized he would have to fork out a fourth of what he made in a month on his little boy’s tuitions. His wife worked as a tealeaf picker at the same garden, and that ought to cushion the pressure a bit, but…

“There is a cultural change happening in the gardens in Darjeeling,” Ashok Kumar, owner of Goomtee tea estate, told me later when I met him in his Calcutta apartment. “There is 100 per cent literacy in the gardens. This wasn’t the case earlier.”

The Darjeeling administrative district – with its three main urban hubs in the hills: Darjeeling town, Kurseong and Kalimpong – have for long been known for its elite boarding schools that were set up during the Raj. Princes and princesses of the erstwhile kingdoms of Sikkim (now an Indian state) and Nepal and Bhutan (now democracies) have studied in one or the other of these.

As did two Hollywood stars: the late Vivien Leigh, who was born in one (St Paul’s school) and studied in another (Loreto Convent), and Erick Avari, a St Joseph’s, Darjeeling alumnus who has acted alongside Richard Gere in Hatchi, Adam Sandler in Mr Deeds, and Brendan Fraser and Rachel Weisz in The Mummy. Moreover, Singer Peter Sarstedt went to Victoria Boys in Kurseong.

This is, of course, apart from a clutch of renowned names in India’s sporting world, the armed forces and industry that have been groomed in these schools. The trend is obviously spreading among the blue-collared of the tea gardens and little towns such as Sukhia that dot the Darjeeling hills.

“Hundred per cent literacy” that Goomtee’s Kumar spoke of was an assertion I also heard at the various gardens I had visited earlier. Harkaram Chaudhary, manager of Namring tea estate, told me there are four schools in the area around his garden, including a high school. “All our children go to school,” he said.

The schools around the gardens are mostly government-run, but as we witnessed at Mim, it could also be privately-owned.

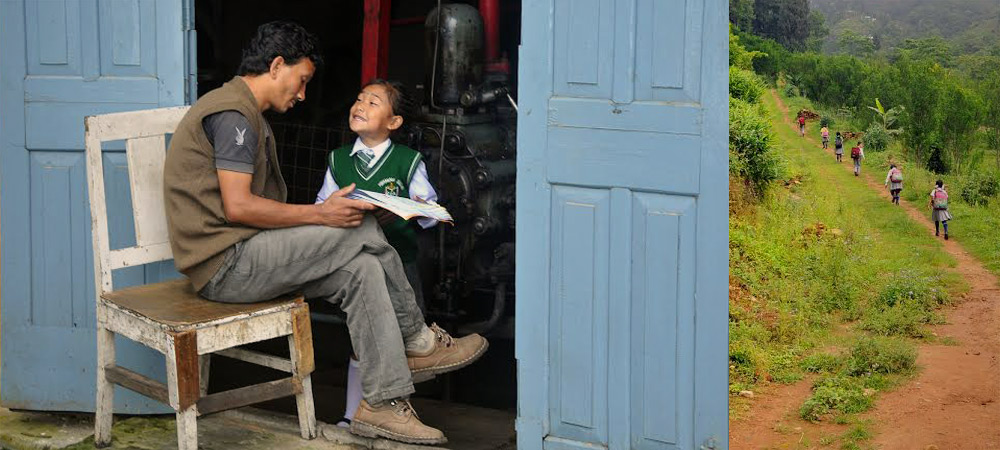

At Goomtee, I saw little children in school uniforms trooping out of a yellow mini school bus, or holding onto their mothers’ hands as they wound their way home, or as one child did, give her father an update in the generator room on what she had learned that day.

Their story was no different elsewhere. Just before reaching Mim tea estate, we saw a two-storey school building downhill; it was a high school lying cheek by jowl with the Mim workers’ colony. Apparently, there was another in the area.

The next day I was at Avongrove tea estate, and chanced upon a group of primary schoolchildren when the manager, Debojit Nandy, was driving me around his picturesque garden. The kids, no more than 10 years old, were being chaperoned home in the workers’ colony by their sole teacher, Surendra Gupta.

Gupta, 33, has its roots in north India but was born in the hills, and speaks Nepali like a local. He told me he was the only teacher at the 24-pupil school currently, the headmaster having retired recently. Why so few students? “There are five primary schools here, how will I get pupils?” Gupta said.

We also came upon a four-storey structure, and uncharacteristically for the region, sporting a lot of glass and chrome; it too boasted of a fairly big playing field. I was told it was “affiliated to Don Bosco”, a private chain of schools with branches across India and abroad.

The place was closed for some reason that day, and I could not meet the administrators or teachers to verify the “Don Bosco angle”. But the modern design of the structure reflected only one thing: the administrators expected to be solvent by catering to families working in the gardens.

When I visited Jungpana tea estate, I had to climb some 600 steps to reach the factory; I had talked of it earlier. On my way down, I met a woman – a garden worker off duty – while she was taking a breather during the steep climb.

“It is so tiring,” she told me in Hindi, a language more or less understood across India but not native to either her, or me, a Bengali. “My children do this every day,” she said.

I had met the woman on the first day of my weeklong trip across the hills, and had the chat with Prashant Gurung on the penultimate night. Their respective stories, and the ones in between, had a common thread: the plantation workers want their children educated.

Yes Mr Kumar, I agree. There may or may not be 100 per cent literacy in the tea gardens – I have no census data on the subject – but of this I am now convinced: there is indeed a cultural change unravelling in the gardens.