Mid morning, 36 degrees C in Chennai and I arrived for my interview with S. Muthiah – writer, journalist, cartographer and chronicler of the European era in South India, especially Chennai.

“This is too early for me,” he said, as an opener.

I swallowed my smile and looked brightly at him, feeling like I was back in his reporting class. I had approached this interview with so me trepidation; after all it was Muthiah who introduced me and a handful of others to the mysteries of the inverted pyramid. Yes, how to write a news story.

These journalism classes were held in the evenings at Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan in Mylapore, next to the Kapaleeswarar Temple. At that time, there were two things I looked forward to – one was Muthiah’s class on reporting, which was practical and to the point, and the other was the walk down East Mada Street after class. The entire stretch of the road would be lit by ‘Petromax’ lanterns; the fragrance of jasmine from the many flower sellers mingled with the smell of frying peanuts while ladies draped in silk saris bargained with the small vendors selling fruits, bangles, beads or kumkum powder. It was as if the entire place was caught in a time warp; it could have been a hundred years ago, and nothing had changed.

Coming from the hills, this was new and strange and wonderful.

Four decades have gone by since then. And, in that time I have wandered through copy departments of ad agencies, raised two boys and through sheer serendipity found myself as a business reporter with a financial daily.

In these years, Muthiah wrote 40 books and became the chronicler of Madras (now, Chennai) and her history. For most Chennai folks, Muthaiah has been the window to a past that was fascinating and also wonderfully told. Through his columns he introduced us to people long gone, whose names are still on street signs and letter heads.

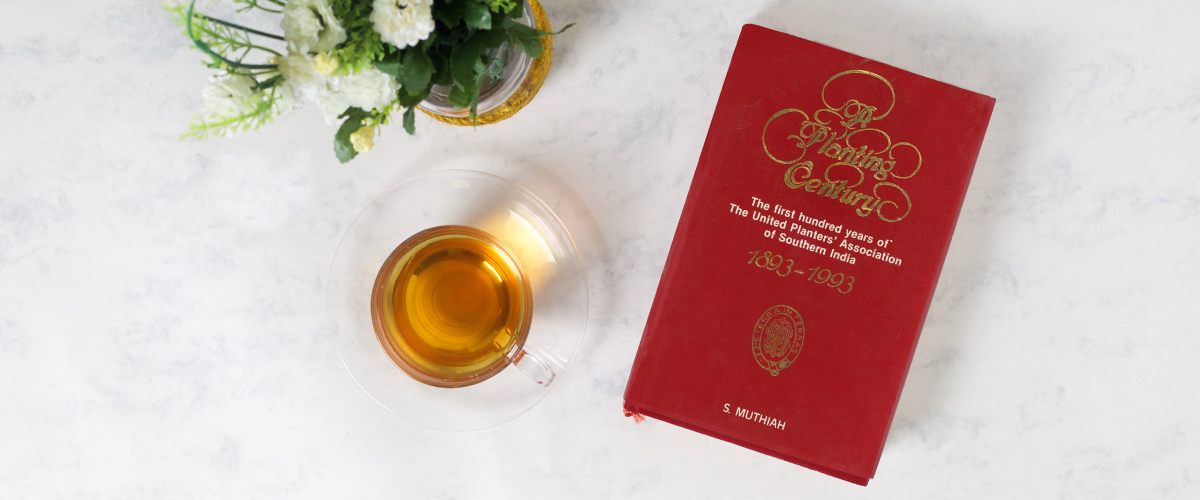

But today, I was on a quest, to tap into Muthiah’s intrinsic knowledge of the tea industry, his associations with planters and his impressions about life on a plantation. After all there aren’t many who can claim to have chronicled the hundred years of plantations in South India. (S. Muthiah “A planting century: the first hundred years of the United Planters’ Association of Southern India, 1893–1993.”)

So, there I was, in his quiet, book-filled home in a corner of Chennai’s busy Thyagaraja Nagar, popularly known as T. Nagar. The traffic sounds receded as Muthiah spoke about his passion: biography as history.

“My contention is that every one of us has a story to tell. We have lived through different periods, experienced different things; lived through various situations…I feel all this has to be recorded, not always for publication but for children and grandchildren, to know what you have lived through.

If you were to look at my life for instance, if I was to talk about my Sri Lanka days, nobody would realize how great life was then…. Today, everyone knows only about the turmoil and the trouble, nobody knows about the wonderful old days… this need to be recorded.”

Muthiah, whose association with the tea industry, both in Sri Lanka and the Nilgiris, started with visiting friends who were planters, is well placed to compare and contrast the two well-known tea growing regions.

“I have been visiting tea estates from as early as 1948, in Sri Lanka first and then in the Western Ghats and in the Nilgiris. The Sri Lankan estates, previously British owned, are beautifully kept but what strikes you most are the beautiful bungalows in which the planters lived,” Muthiah said.

In both the countries, the estate bungalows are remarkable examples of hybrid architecture- a mix of Victorian England’s country homes embellished with local carpentry and masonry work. These beautiful bungalows would be set amid lovely gardens lorded over by a Periya Dorai (Senior Manager) and his wife, be waited on by an army of servants. These were the things a casual visitor saw and thereon believed that the life on the estate was always grand.

“But things were not always quite like that. People often forget how difficult life was for the pioneering planters in the early days on the Western Ghats and in the Nilgiris. The early planters, were like the frontiersmen in the Wild West, they cleared the jungle, fought off wild animals and lived like their labour did, in huts and later in log cabins. The pioneer planters who opened up the estates were doughty individuals who invested their own money and life to planting. More often than not, they died before they reaped the benefits of their hard labour, or sold out to companies who had money and muscle.

Over a period of time, life on the plantations evolved into an exclusive world where the Periya Dorai was the ruler of all he surveyed, the Chinna Dorai (Assistant Manager), his trusted lieutenant while the Visiting Agent represented a higher power – that of the company bosses or boxwallahs who lived in faraway Calcutta, Madras or Cochin.”

As Muthiah speaks about the lifestyle on the estates, I am reminded of the parties in those far-flung Nilgiri estate bungalows that my parents went for; grand affairs all of them, with fairy lights on the lawn, uniformed waiters moving silently among the guests with trays of hors d’oeuvres, the ladies in their Mysore silks and chiffon saris with matching stoles and stilettos and the men in their suits and crocodile leather shoes, with Cuban heels. And how they danced the Cha Cha Cha or the Fox Trot, until the sun came up, to the music of the Enos Brothers!

“Of course, even today, there is a stark contrast between how the Periya Dorai lives and what used to be called the ‘coolie’ (today the politically correct word would be labour) lines,” says Muthiah. The living conditions for labour were far better in the Western Ghats than in Sri Lanka, he remembers.

Most of the early planters in the Nilgiris, had already done a stint in Sri Lanka (Ceylon as it was known then) where crops such as coffee and tea were planted earlier than in India. Once the estates were opened up in the Nilgiris, many of these planters, seeking greener pastures, came over bringing with them their Ceylon experience. Ceylon, for instance, had already gone through the terrible process of coffee blight (In the early part of the 19th Century, most of the Western Ghats was planted with coffee; this changed when a disease attacked the coffee plants and wiped out most of the estates.) which the Nilgiri planters were yet to experience.

Along with the planters came craftsmen, such as, carpenters and masons who built many of the old buildings in the Nilgiris. So, this much talked of Nilgiri roof, which still graces most of the estate and garden houses in Ooty and Coonoor, like the Carrington bungalow, as well as some of the old churches, are actually the handiwork of carpenters from Ceylon.

Today, says Muthiah, it is fashionable to talk how the tea plantations have created ecological problems quite forgetting that at one point, the entire economy of South India was dependent on tea.

Suddenly, he stopped and looked askance at my phone with which I was recording and asked, “Are you expecting a call?” I reassured him that I was not and was recording the interview as a back up to my notes.

Muthiah has a distaste for modern gadgets like cell phones and computers and still prefers to write his weekly column on his trusted old Remington. He says, “When I visit my daughters, I am forced to use their laptops and it takes me three days to write my column. It takes me just three hours to type it out on my typewriter.”

Our conversation tapers off as we both seem to be remembering things and places, me of the blight that destroyed my father’s coffee crop, of growing up in the Nilgiris… But I do ask Muthiah why and how he became a chronicler and historian.

“By the time I started talking about it, I realized that I have been already doing this in different ways. It was a bit of chicken and egg situation …. I got into this unwittingly. I first started writing about Madras in the 1970s. I spoke on this subject in many forums… how it was not just people that needed to record history, but also institutions. It has now become a kind of specialization with me.”

And right there, I know, is another story waiting on the wings. I make my leave but with a promise to return.