Most evenings, the talk is about tea, the weather and the prices of green leaf in Kotagiri and Silas. Then there is also talk of how someone is selling and someone else is uprooting tea and building villas. Sometimes, a Young Turk talks about the importance of branding and marketing while the older ones listen impassively. New methods, newer people for an old industry; the Coonoor Club is the planter’s primary watering hole in Coonoor and has been since 1885.

Nothing much has changed. Tea is still top dog; real estate is richer but underdog all the same. A small difference, the planters these days are not English, Irish or Scottish, they are Tamil, Badaga, Kannada, Malayalee, Gujurati and Sikh.

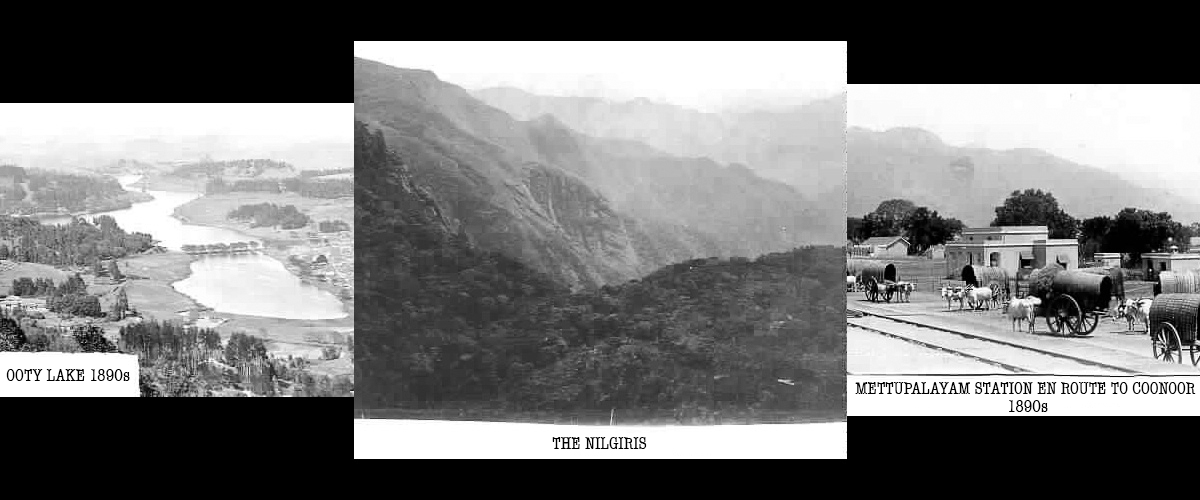

Coonoor is where the Nilgiri tea story started. It is a story which has been retold many times and yet not lost its charm.

The earliest recorded visit by a European visitor to the Nilgiris was by in 1603 by an Italian Jesuit, Giacomo Finicio who wrote to his superiors (the original letter is in the British Museum), “Barren mountains and valleys without a fruit tree or wild tree except in certain damp places where there were a few wild trees. The whole country is a desert and the land and the climate are very cold”. He was referring to the shola forests and grasslands on the plateau and higher slopes. His view that these were wastelands was upheld by the British and subsequently by the Indian policy makers. This was to have a disastrous effect on the ecology of the hills.

Between 1804 and 1818 a number of Englishmen ventured up the hills and reported “the existence of a tableland with European climate.”

The Nilgiris which was until then a part of the Kingdom of Mysore was ceded to the British East India Company after the defeat of Tipu Sultan in the fourth Anglo Mysore war in 1799. There are two reasons why the Nilgiris is called so; the first is the smoky blue haze which covers the hills when viewed from the plains and the other is the flowering of the Neelakurinji (Strobilanthes) once in twelve years which carpets the hills with purplish blue flowers.

In 1819, John Sullivan, the Commissioner of Coimbatore, led an army contingent up the steep slopes of the “Neilgherries”. It took them six days of climbing very steep slopes and six deaths before they reached the Kotagiri plateau. His mandate was to discover whether the tales about the hills had any truth to it. He discovered the truth and more. The cool air, fragrant with the scent of flowers, the streams, the rolling grasslands and shola forests so enchanted Sullivan that he decided to build a house for himself here; which he did the following year.

After John Sullivan’s expedition, another set of explorers went up to check the temperature which in the shade in the noon was 23 degrees Celsius while the temperature in the plains was 38 degrees Celsius. Even after Sullivan’s visit, few Europeans believed that such a cold climate within the tropics was possible.

Sullivan and the Europeans preceding him found the hills sparsely populated. The people of hills were Todas, Badagas, Kotas, Kurumbas and Irulas. The Todas who are pastoral people lived in munds (hamlets) which could be found all over the plateau, while Badagas who are agriculturalists (and non tribal) are the largest of the indigenous group. The Kotas are potters, blacksmiths, carpenters and musicians; the Kurumbas are hunter gatherers while the Irulas are snake charmers and work as labourers during sowing and harvesting.

Sullivan petitioned the Madras Government to make the hills a sanatorium for the English troops. The next ten years saw a large number of British relocating to the hills.

Francis, ICS, records this apocryphal tale:In 1833, Dr. Christie, an Assistant Surgeon from Madras, on special duty in the Nilgiris, conducting meteorological and geological investigations near Coonoor, noticed camellia shrubs which closely resembled the tea bush, grew abundantly near Coonoor. (Planters whom I spoke to had rather conflicting views on whether camellia was a native of Nilgiris or not; some felt that this variety closely resembled camellia assamica, the tea found in Assam, while others were of the opinion that the camellia was not a native plant of the Nilgiris. Most of the planters felt that many of the plants endemic to the Nilgiris were wiped out with the introduction of so many exotic varieties.)

Coming back to Dr Christie… he applied for a land grant to plant tea and also ordered for tea seeds from China. But he died before the seeds arrived. When the seeds did arrive they were given to other Englishmen experimenting with tea in other parts of the Nilgiris.

Two years later, Lord William Bentinck, Governor General of India, felt that there was a future for tea in India, set up the Tea Commission and sent them to China to bring back tea seeds and expert tea makers. These seeds from China, when they finally arrived, were planted in an experimental farm in the Ketti valley, which lies between the towns of Ooty and Coonoor.

But the experiment was a failure and the farm was closed down in 1836. The mansion in Ketti (currently the women’s hostel of the CSI College of Engineering, Ketti) was leased out to Le Marquis de Saint- Simon, the Governor General of French colonies in India. The French botanist Georges Guerrard-Samuel Perrottet, in the employ of de Saint-Simon found nine tea plants, stunted, a few inches high but alive. He replanted the seedlings and nurtured them and in two years, the plants had grown to almost four feet in height. These plants were healthy with flowers, seeds and young leaves. He published an account of this in the Asiatic Journal which attracted a lot of attention.

In 1840, tea, made from the Ketti plants and from plants in Billikal near Kotagiri, was sent by John Sullivan to the Madras Agri-horticultural Society. The method by which this early tea was made would make today’s connoisseurs shudder. The leaves had been dried in the open and fired in a frying pan; yet the tea was “pronounced excellent” by the experts in Madras.

Sometime later, a planter named Henry Mann succeeded in making fairly good tea from the Nilgiri plants. He was so encouraged that he ordered for better quality seeds from China, hoping to improve the quality of the tea. Although it was still difficult and time consuming to procure tea seeds from China, he got some seeds, purportedly from some of the finest gardens in China and planted them near Coonoor; this estate was called Coonoor Tea Estate. In 1856, the tea manufactured from this estate was favorably reviewed in the London auction. But, by this time, Mann was a disillusioned man. The land under tea cultivation was not enough for him to make a profit and his requests to lease out more forest land to plant tea, were denied. So he gave up the experiment.

Around the same time that Mann was planting his tea near Coonoor, a man named Rae was planting an area near Sholur close to Ooty. This estate, Dunsandle, is at an elevation of over 1828.8 m and is now owned by the Bombay Burmah Trading Company.

Like Dunsandle, some of the early estates are still there; many of them have preserved their old China bushes, more for the interest of botanists and tea historians. Thaishola (meaning mother of the forests) Estate was opened in 1859 and was one of the two camps for Chinese prisoners of war in the Nilgiris.

Some Chinese prisoners of war were brought to Nilgiris after the second Opium War (1856-1860) and some others were from the Straits Settlements which include Singapore, Malacca, Dinding and Penang. The prisoners were initially sent because of the overcrowding in the Madras jails. Later, when they were found to be good workers, they were sent to work on the cinchona plantations in Naduvattom and in tea estates. It is not known whether these Chinese prisoners had any previous knowledge of tea planting or manufacture or how they contributed. Sir Percival Griffins, tea historian says “it is an improbable legend which stated that these Chinese prisoners were responsible for instructing these planters in the manufacture of tea”. Chinese prisoners were used to plant Thaishola Estate which even today has a Jail Thottam (meaning jail garden).

Meanwhile, Dr. Cleghorn, the Conservator of Forests noticed that tea plants were growing well and petitioned the government to bring in a trained Chinese tea maker from the North West Provinces. Maddy’s Ramblings, a well researched blog, quotes a letter from Superintendent of the Dehradun Botanical gardens to the Conservator of Forests which says that he has no Chinese tea makers to send to the Nilgiris but that he can send native trained people instead on a three-year contract.

But this was shot down by then Governor of Madras, Sir Charles Trevelyan, who felt that the planters were being spoon-fed. Later, when Sir William Dennison was Governor, he did send for experienced tea makers from the North West Provinces and also imported seeds. But by and large, the planters were left to “work out their own salvation”.

My father P.C.Kurian, a second generation tea planter used to tell us about how hard the lives of the early planters were. “They, (the early planters) lived in mud and grass huts while they cut down large tracts of forests and ploughed up the grasslands to plant tea. They battled with malaria and wild animals in the forests, subsisting on rice gruel and wild game which they shot. They rode horses and in most part walked along the elephant tracks through the forests looking for places to plant tea. The planters those days had to bring labor up from the plains and then stand guard over them so that they didn’t run off.”

Their efforts paid off and by end of the nineteenth century there were about 3000 acres of land under tea. At the Ooty Agricultural Show that year as many as eighteen planters were able to showcase their produce. James Wilkinson Breeks, the Commissioner of Nilgiris at that time, suggested that some of the teas be sent to London for the opinion of the brokers. The planters acted on his advice and the teas were dispatched to Mincing Lane in London, (the world’s leading center for tea, opium and spice trade) where the teas were pronounced ‘good’ and ‘very good’. The value of the teas ranged from 1s.4d (1 shilling and 4 pennies) and 6s per pound of tea.

The planters tried to create a local market for tea among the natives, to get rid of the middle men in London, who were taking away a large portion of the profits as their commission. However, tea drinking among Indians took a long time to catch on, so the planters continued to be at the mercy of middle men in Mincing Lane.

The acreage under tea grew every year as more sholas and grass lands came under cultivation. The planter’s lifestyle which was once austere became lavish. Beautiful bungalows overlooking pristine valleys, waterfalls and mountain peaks were built to accommodate the managers. The bungalows, little oases of elegance and class, had tennis courts, dance floors, bars and even Royal Doulton commodes. The estate gardens became a category in itself as managers’ wives vied with each other to bag the prize for the best estate garden at the Ooty Flower Show.

While they danced, played and planted tea, the world around them changed.

Photographs sourced from the web, licensed for reuse on Creative Commons.