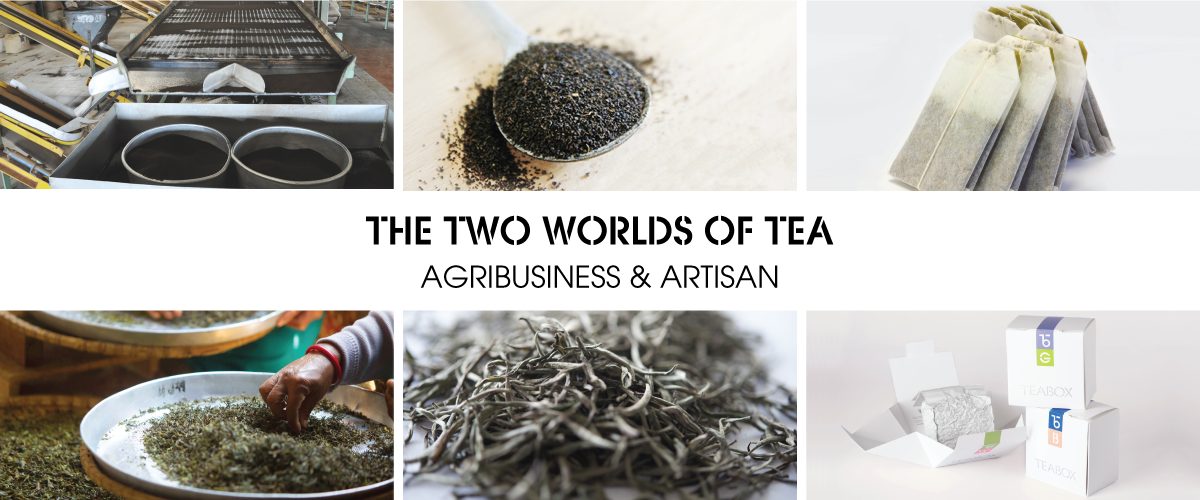

Here’s an image showing two different teas: whole leaf and dust used in the tea bag. Both are in the same broad price range: 25-40 cents a cup for the leaf tea and 20-40 for bags. But why do they look so different and does it matter much in terms of your enjoying your tea and getting good value in shopping for it?

There are two paths from the tea bush to your cup: Artisan and Agribusiness. The direction of the path is set by the harvesting of the leaf and its separation from the bush. If it’s selectively plucked by hand, that’s in effect a commitment to nursing it to bring out its distinctive character, whereas grabbing and chopping it up precludes taking the Artisan route.

The top banner illustrates the two paths for making black teas, which is around 85% of the global market. Both share the starting point – the leaves on the tip of the bush branches. (The details for green teas are different in detail but directly equivalent.) The choice of path very much depends on the terrain. If the soil, climate and mountain location produce a leaf that is especially full of the compounds that can be manipulated to make a premium tea, producers take the Artisan path.

They pick the Agribusiness one if the leaf is of lesser quality when still on the bush and can only end up as a commodity tea that must compete in export markets dominated by falling prices and overcapacity. In many instances, there is no real choice. The terrain, bush and leaf are not superior enough to command a premium position in the market and the competitive and financial strains make hand-crafted individualized quality unaffordable.

The key choice: Orthodox versus Cut, Tear, Curl

For black teas, the basic choice that determines every later step is Orthodox processing versus Cut, Tear and Curl. Green teas are made differently, because they do not include the oxidation step that regulates the chemical interactions of the leaf with air. The tension is the same for all teas, as is the response: the Artisan-Orthodox method preserves the harvested leaf and moves it slowly through to the finished tea. Agribusiness-CTC speeds it up by breaking it up. It’s a little analogous to beef butchers; Orthodox steaks permit more options in aging, grading, cutting and use than ground beef. Once the chopping and mincing starts, there’s no going back.

The analogy translates well visually. The key no-going-back step in CTC comes between the withering of the harvested leaf to reduce its moisture and the oxidation to build its flavors and color of the tea. Orthodox processing lightly rolls the leaf to start breaking up its cell and releasing enzymes to catalyze oxidation.

CTC launches a full force assault. The central machine is the rotorvane, a set of fast and powerful rotor drum cylinders rotating in opposite directions. The teeth “macerate” the leaf after conditioning it to clean it up so it can be fed as a continuous stream of leaf; secondary leaf and the broken pieces and dust are recycled and mixed into the flow. The rotorvanes shape the leaf into pellets of uniform size; rollers with sharp grooved cutters reshape it to look leaf-ish. The crushers and tearers operate at speeds of up to 600-1200 revolutions per minute.

This is a very efficient process and without its introduction in the 1950s the black tea industry could not have been economically viable for the mass market. It cuts processing time in half, produces a fuller, darker – and largely more bitter – brew, and gets a higher yield per hectare of bushes. It is far more cost-efficient, especially when combined with machine-harvesting. 60% of the total production costs of traditional tea farming has been for labor.

So, CTC is more productive and efficient. It is used to make 80% of all black tea with is around 80% of the total global market. Something has to get lost in all this: complexity of flavor. This is instant coffee versus ground beans. The core aspect of every move from Artisan to Agribusiness is standardization. That, by definition, means reducing variance and establishing a baseline average.

The owner of one of the best estates in Darjeeling captures what determines the teas that get into the mass outlets and those that don’t and won’t: “The [largest global brands] are blenders and packagers – so they can never provide good recognition to individual gardens and boutique properties. The major blenders buy medium quality teas to make a standard tea so that they can offer a consistent blend at all locations 12 months in a year.”

The brands can counter with their strong logistics capabilities. Buying Chinese teas is a muddle, gamble and frequent con game. The best Agribusiness brands deliver a consistent and reliable product, well packaged and obviously meeting the preferences of many consumers.

Flavored teas: the search for differentiation

The CTC/Orthodox choice drives all the later processing steps. It is also the point where too much of the marketing sleight of hand begins. Agribusiness packagers can evade the question of how good is the leaf just by putting a name on the end result. Its anonymous average ingredients then are touted as a nonaverage blend of fine teas, natural tea, and sometimes an “exclusive” tea. They add adjectives that are more poetry than descriptors: premium blend of, a Royal something, a full-bodied, fragrant, bold, rich, traditional or exotic – a word that often means equates to “weird.”

More and more low end Agribusiness tea – CTC black and simpler and highly automated green tea – can be differentiated only by adding something to it. This means giving some nonaverage flavoring to decidedly average leaf. Exotic examples abound, with elegant ways of implying that the enhancement to the base tea ingredient is hand-picked from the garden or the tea-chef’s culinary flourish: Chocolate Earl Grey and Melon Tranquility Green.

Flavored teas, including Earl Grey, are one obvious form of differentiation. One Blackcurrant Exotic Earl Grey sells at 40 cents a tea bag – twice the seller’s plain Ceylon breakfast tea (22¢) but without its “unusual flavor” (the ad plug) doubled markup for the blackcurrant enhancement, which is “set in an organic alcohol base… include[s] a vegetable glycerin component.” (That’s not in the ad or on the package: the flavor supplier’s description.)

This additive is described as “natural.” That simple commonsense word that suggests health and goodness is doubletalk. Chemicals that are “nature identical” to the compounds they mimic can be as legally acceptable as they are for foods in general. They are cheaper to make, safer in many instances, and more consistent and reliable. But many of them are mainly used to fool the senses and boost mediocre tea ingredients. You should not be paying a premium for them.

Artisan tea is naturally natural. It doesn’t have additives. The Artisan path down the mountains begins and ends with the very same leaf that is morphed but not augmented on the journey. The only flavors come from a few teas which are very delicately infused by fresh petals placed among the leaves.

Those make for some of the most pleasant, soft and balanced teas on the market: China jasmine pearls, rose congous, Moroccan mint and jasmine white Silver Needles. Several of the tea brands that target the tea drinkers who want the freshest of flavors specialize in the art of blending, including Earl Greys and floral/fruity greens. These all combine leaf and petal, not dust and additive. The scenting process is laborious and lengthy, anywhere from 24 hours to many weeks.

The picture above shows a spoonful of dust tea. It doesn’t taste as good as the Jasmine Pearl. Technically, it should. It’s natural and organic but that doesn’t compensate for the blandness of the base ingredients and the processing. Several reviews write about first coming across jasmine green tea bags in a Chinese restaurant. Do you recall ever being impressed, delighted and eager to buy the tea served with your dim sum?

Tea prices

Prices obviously are lower for Agribusiness than Artisan teas – in most instances, but by no means all. Here are the approximate ranges:

Standard name brands in the supermarket: 20 cents per bag up to 40¢ for fancy ones and blends in tins. There are cheaper ones, just as with hot dogs that contain meat byproducts.

Good grade whole leaf: 30 cents a cup. (Sold in units of grams and ounces: 30¢ equates to $4 an ounce and $15 for 100 grams.)

Pedigree special teas: 50-70¢. Typically, these are sold in 4 ounce or 100 gram (3.5 oz), $20-40 a purchase unit. That sounds a lot, but many of these, specialty whites, puehrs and oolongs, can be re-infused a number of times. You’ll get at least five cups out of a spoonful of Big Red Robe oolong.

There are wide price variations especially in the egregious markup of blends in fancy tins and the take-it-or-leave-it premiums for very high end rare teas. There are also plenty of really good deals among mid-range whole leaf teas.

Once you get a sense of what to look for in a tea and pick out a few reliable online suppliers, you will pay less for good quality whole leaf tea of much better, fresher and nuanced flavor than you shell out for high end tea bags. Equally, if you want much better tea than you get in the supermarket, the extra cost for outstanding Artisan pedigree teas is $5-10 a week for three cups a day.

Choosing the path

It’s hard to argue that Agribusiness teas in any way match Artisan ones. That’s of no matter if you drink only the occasional cup, are happy with most bags, and want no hassle dunk-and-drink convenience. The contrast is rather like hot dogs (bags), burgers (tins of CTC), and steak (Artisan whole leaf). Hot dogs are tasty and versatile. But they do not make for a healthy diet, many are loaded with nitrites and lower even lowest grade meats and their infamous byproducts, and not worth paying a premium for. (The equivalent of Earl Grey perhaps: Marquis of LaFayette pork wiener, from the recipe he brought to Valley Forge, prepared especially for General Washington? Sure.) Nor should the packaging obscure the contents. Green tea dust is green tea dust whether it’s in the package with the pagoda and beard-stroking sage.

The key to enjoying tea beyond the hot dog equivalent is to get as close as you can to paying for the leaf and not the marketing, packaging, retail outlet or name associations. That means knowing something about the leaf. Many tea drinkers have almost no knowledge of the basics here and that means they buy only on the basis of the other factors, mainly brand name recognition.

And what makes the great stuff so good. If you want really good tea, focus on the leaf. If the labeling, pedigree, name and sourcing information don’t specifically describe its Artisan features, it’s Agribusiness. If it’s in a tea bag, it’s hot dog, not steak. If it’s flavored, be wary.

This doesn’t demand a lot of effort or expertise. The best vendors, blogs, catalogs and stores will give you the basics; if they can’t or don’t, there are plenty of other places to look. It’s no different than wines. Yes, it takes decades, a sensitive palate and nose, plus a healthy bank balance to become a real expert. But, just as wines are all about the grape, the region, and the producer pedigree, it’s the same for tea.

Photograph of dust tea source: Noor AlQahtani