McLeod Ganj is a beautiful little town in the foothills of the Himalayas with Tibetan temples and pretty stores and quaint cafes. For the tourist, there’s plenty to see. But topping my list was Bookworm, a bookstore run by Lhasang Tsering. I’d heard about him, heard that he was a highly opinionated and interesting man. Tibetans are not best known for their love for books or a desire to read—theirs has been a tradition of oral storytelling. So, already I was intrigued.

I went down to Bookworm four times in five days. But on each visit, I only saw shuttered doors and I was beginning to think the store was a thing of the past. One last try, I told myself, and it was fifth time lucky.

Bookworm is possibly the most organised bookstore I have ever walked into. Not a book out of place and every book you pull out to browse seems to magically return to its designated place on the shelves. Fiction rubs shoulder with non-fiction and Tibetan Buddhism and philosophy. Second-hand books are placed with their spines up so that you can read the titles without toppling the carefully constructed book tower. Of course, you are not discouraged to pick them up but don’t be surprised if they return to the exact same spot a few minutes later.

I wondered vaguely about the owner and his OCD but when I looked for him, he was not to be found. Behind the counter stood a young Tibetan, who, as it turned out was Lhasang’s nephew. He told me that his uncle was no longer involved in the day-to-day workings of the store, busy as he was with his own book. When I asked the nephew about meeting Lhasang, he appeared nervous. At my insistence, he reluctantly took out a card with a number.

Clearing his throat, he said, “Don’t wait for Uncle to fix the time and place. You tell him where and when. Don’t leave it to his convenience.”

“Okay, I said.

“Don’t interrupt Uncle. Let him finish his sentence…” As I nodded, I heard, in almost a whisper, “He hates being interrupted.”

I was beginning to feel rather intimidated by Lhasang’s reputation and spent the day researching the ‘dreaded uncle’. Then, I did exactly as advised, calling Lhasang and fixing a meeting for the following evening. Even as I began to explain the context to our interview, I realised that Lhasang had hung up. Later, I learnt that he hates speaking over the phone.

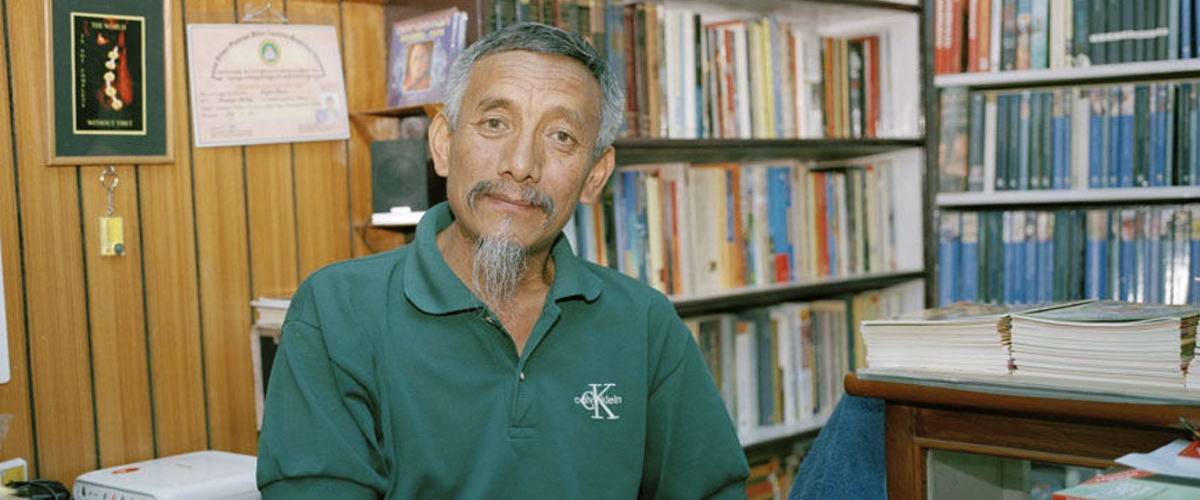

I was unusually nervous for the interview and arrived at the Bookworm 15 minutes early. It was, again, shut and I waited on the steps outside. Lhasang arrived on time, a skinny man, wearing a backpack, and well, smiling pleasantly. We exchanged greetings and before I knew it, he was guiding me to the garden café at Hotel Bhagsu run by the tourism department. We were talking about tea, laughing easily, enough for me to forget my earlier misgivings.

“I call myself a tea-totaller in every sense. I drink a lot of tea and had for many years replaced my evening whiskey with it.” he said, on hearing that I was interviewing him for a tea blog.

The garden café at this slightly dilapidated hotel was empty but it was a good 15 minutes before someone came to take our order. Lhasang seemed unperturbed at this slowness, as though patience is something he has enormous stores of.

We ordered chai. “I don’t drink Tibetan salted tea,” he added. “I can burn the sugar by walking, but not the salt.” Unsure if I should interrupt to ask what he meant by that, I chose to let it pass. And instead watched him rummage through his backpack. He pulled out two bookmarks with poetry printed on them. Offering them to me, he said, “This is propaganda disguised as bookmarks which I distribute to everybody I meet. Also, my printer gave me a bunch of free copies.”

[bctt tweet=”We ordered chai. “I don’t drink Tibetan salted tea,” he added. “I can burn the sugar by walking, but not the salt.””]

I accepted with thanks. He talked of his life, being brought away from Tibet into India at the age of eight, his days as an activist and his views on the future of his countrymen. Clearly, he holds contrarian views on the politics of his people. He’s ready to criticise his leaders. “I am working on a book tentatively titled No, Your Holiness. No! that talks of why I disagree with the Dalai Lama,” he adds.

I was more interested in his bookstore but he would rather talk about his activism. It was a friendly tussle and we were both smiling as we sparred. I understood his desire to be an activist but I was curious about the bookstore.

“I read a lot of fiction in my youth,” he explained. “While children were thronging movie halls on weekends, I was up in the mountains with a book under the clouds. When I knew I wouldn’t go back to a job with the administration and had to do something to make a living, I thought of a bookstore. A second-hand bookshop, in a tourist driven economy, so people have something to do once they go back to their hotel rooms post sundown. This was in the late 80s and there were no TVs and mobile phone then.”

The first books arrived through a friend who ran a bookstore by the same name in nearby Manali. As early as the second year, Bookworm became more than a secondhand bookstore. Recommendations came from backpackers visiting the store and Lhasang paid attention to them, building a curated and interesting mix of titles.

But Bookworm was clearly never just a bookstore for bored tourists. For Lhasang it was the vehicle he chose to pursue his activism. “The purpose of the bookstore was also to dispense alternate information about the Tibetans,” he said. It gave him a space to articulate his thoughts and engage in conversation with people who stopped by. With the years, the man and his store rapidly grew into a required stop for the visitor interested in history, politics and religion.

[bctt tweet=”I am exercising the last human right to not be driven insane.”]

While a bookstore was profitable business in the early years, like indie bookstores world over, the Bookworm too has seen a downturn in the last decade. The backpackers have trickled down in numbers, and the few who do arrive head for the bookstores in the monasteries. And Lhasang, now 64, is questioning his readiness for a retired life.

“I am well, and that is my problem,” says the bookseller-activist. It is hard to be well and have no purpose. I can no longer listen to my leaders and I can no longer stay silent. I am exercising the last human right to not be driven insane.”