Here’s a short summary of the introduction of tea to Europe. You can surely guess which country it refers to: the first nation whose ships brought tea from China in large quantities. The drink rapidly became fashionable in upper class circles. Tea was first sold in its apothecaries and within a few years tea houses spread across its major cities. It accounted for about 90% of the tea imported by the North American colonists and almost 70% in what quickly became the largest market in Europe. It was a major factor in the Boston Harbor Tea Party that is the emblem of the start of the American Revolution.

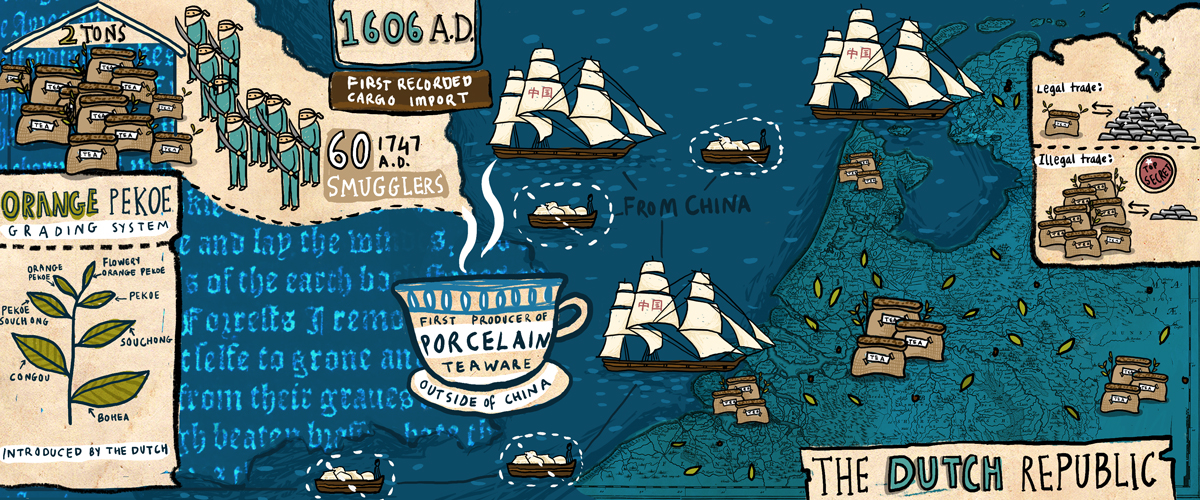

It also pioneered the growth of tea in its Asian colonies, created the orange pekoe leaf grading system, and was the earliest producer of porcelain teaware outside China. It led to the welcoming ambience of tea as we know it: “Would you like a nice cup of tea?” This all began in the very same year as the first recorded performance of the world’s greatest play, Shakespeare’s King Lear, in 1606.

But…Shakespeare never drank tea.

Tea didn’t reach England until the 1660s; Shakespeare died in 1616. Had he been Dutch, however, he would probably have come across it in his family home. A nice cup of tea? Earl Grey? English Breakfast? Uh, no… “Een lekker kopje thee? Graf Grijs? Engels Ontbijt?” Jawoord.

Every one of the facts, firsts and figures listed above refers to Holland, now the Netherlands, not to England. From the 1600s to the end of the 1700s, tea was Dutch. Its first recorded cargo import was 1606 (from Japan); the earliest reference in Britain is 1658.

Portugal was the other early pacesetter and the creation of the ceremonial aristocratic English high tea tradition is credited to Princess Catherine of Braganza, who married Charles II. That didn’t have any real impact on stimulating tea consumption, though it began the mythology of “English” tea. Most people are unaware that tea has never been grown in England (except for a tiny gimmick garden run by a descendant of Earl Grey), that the leading global brand of Earl Grey never touches the UK in any stage of production but is made in Poland, that the dominant English supermarket brand makes 2 million tea bags an hour, 24 hours a day – in the desert region of Dubai in the Middle East – or that the second largest English tea firm is actually Indian-owned and operated.

Charles II’s government vigorously opposed tea, attempting to ban its sale in private houses, on the curious grounds of countering sedition. It also made the move that guaranteed Dutch dominance; ultra-high taxation. Tea was already expensive; a pound cost months of the average wages of a laborer. The initial tax rate of 25% (1689) made it unaffordable and was reduced just three years later to 5%.

That began a one-hundred year yo-yoing. Tea was easy – in theory – to tax at the port of entry of the ships that brought it from China. It was a frequent source of funding for wars. As with Prohibition of alcoholic drinks in the US, there were plenty of entrepreneurs who thrived on smuggling.

Apart from the tax load, the East India Company that had a complete government-granted monopoly manipulated supply to maintain prices. It’s not surprising that smugglers met demand at low prices. Around 70% of tea consumed in England was contraband. In the pre-Revolution American colonies, it was closer to 90%. When economic logic finally won out and the import duty was cut in a single step in 1784, from 119% to 12.5%, smuggling dried up very quickly.

The profits on tea were immense, even though prices dropped as volume increased. The markup on China tea was 2,000%. “Owlers” – smugglers – offered it for less than half the East India Company price. The total trade amounted to billions in today’s currency.

Forget the tea and crumpets high tea stuff

Tea was down and dirty big business, with many organized crime rings. The most infamous instance in England has been compared to Chapo Guzman and his Mexican Sinaola drug cartel. In 1747, the Hawkhurst gang lost a shipment of two tons of tea to customs officers, who stored it in the Kings Custom House. Sixty of the smugglers launched an armed attack and recaptured all the tea.

By accident, a local villager was recognized by authorities as knowing one of the leaders. He and an elderly customs officer witness were waylaid by the gang, paraded through dozens of villages while tied upside down on horses so that they were constantly kicked in the face by their hooves, flogged and semi-castrated. They were killed slowly, with the old man buried alive and the other stoned to death after prolonged torture, including cutting off his nose. The gang had terrorized the region of Kent, which had a long and isolated coastline. Villages set up militia as protection. This brutal treatment was a message about the costs of messing with the cartel.

Hawkhurst was an extreme, but not an exception. Tea smuggling was immense in its scale and organization. This reflected tea’s growing and pervasive impact across the population. Later, this led to the two shameful Opium Wars, where Britain forced China to end its efforts to ban the illegal sale of opium from India that funded the purchase of tea for export to Britain. The Chinese would accept only silver in payment and were not interested in buying European goods.

At one point, 35% of all the money flowing through the Bank of England, the equivalent of the Federal Reserve, was for currency for this tea trade. The Opium Wars broke open the market and crippled the social and economic structures of China for over a century; part of the peace deal was the two-hundred year lease of Hong Kong to Britain.

Damn thee, and God damn thy purblind eyes, thou bugger!

Competition between the legal and contraband providers of tea was somewhat intense. Here’s the opening of a letter from a smuggler whose ship was captured in his absence. It’s addressed to the captain of the Royal Navy revenue cutter vessel: “Sir: Damn thee, and God damn thy purblind eyes, thou bugger, thou death-looking son of a bitch… I would drove thee and thy gang to Hell, where thou belongest, thou Devil incarnet.”

The scale of smuggling and the fact that most of the population did not see it as a crime naturally led to a certain amount of public-private sector collaboration: bribes, payoffs and scofflaws. Reports in the 1750s describe refined ladies setting up stalls on the beaches, where they displayed Owler tea in silver caddies for re-sale. A leading merchant in Boston, a deeply religious man, salved his conscience by raising his hand each morning and taking a solemn vow that everything else he stated under oath that day about the legality of his newly arrived goods would be false. So all his lies were true and his contraband left undetected.

Not that detection mattered too much. The population was on the side of the smugglers; of 38 criminal prosecutions brought in one year in Boston, just two resulted in a guilty verdict. A habit among judges in England who had no choice but to convict a smuggler and confiscate his ship was to arrange to divert legal ownership to themselves and sell it back to him for a small fraction of its value.

There were fortunes made through smuggling. An intriguing instance is one of the best-known Founding Fathers of the US, John Hancock. He was perhaps the richest man in the colonies, owning the equivalent of about $90 billion today. He is famous for his ultra-large size signature on the Declaration of Independence that made the term “write your John Hancock” a cliché.

He helped fund the political “caucus” that led the Boston Tea Party’s dumping of tea in the harbor. This was partly self-interest. Popular wisdom assumes that the Tea Party occurred because the import tax on tea had been increased. It was actually cut in net impact, but how it was incurred and collected and exactly where by whom meant that the East India company had found a way to sell tea legally cheaper than Hancock could smuggle it.

Hancock was the man who expected to be appointed to command the Revolutionary Army instead of George Washington. It is intriguing to envisage the Commander in Chief as Smuggler in Chief.

The Dutch provided most of the shipping for all this tea, which would be offloaded by small boats, hidden in churches, disguised as fishing catch, and ferried by packhorse to the market. (French and Swedish operations added a smaller traffic.) Holland’s own trading monopoly, also named the East India company, had set up naval bases and trading stations across Asia by the 1700s and owned the tea and spice trade. It was the first to contract for tea with Japan. In 1684, it set up tea farms in Java, using Japanese seeds.

By the time tea was first imported in bulk to England, it was a standard offer in Dutch inns, taverns and food shops. Holland was also the first to ship porcelain from China and developed its own Delft ceramics.

Orange pekoe, smooch, and bohea

One permanent legacy of the Dutch leadership today is Orange Pekoe tea. This is the base of the leaf grading system that emerged in the late 1800s to classify Indian and Ceylon teas for auction. “Orange” has nothing to do with color. The general consensus is that it refers to the House of Orange-Nassau, the ruling family of Holland, and that it was used by traders and growers to imply a Royal Warrant certification of quality. (It’s ironic to see tea brands now boasting of their Orange Pekoe – it means in essence, just average black tea leaf.)

As its domestic market plateaued and British consumption soared, the role of the Dutch shifted to being the provider that bypassed the East Indies Company monopoly of high prices and higher taxes. All its later tea trade was gesmokkeld – smuggled. It was also verschrikkelijk – terrible. The high cost of tea encouraged adulteration and faking. This began in China, where it was commonplace for producers to add poisonous chemicals to enhance color, such as copper carbonate and lead chromate.

The smugglers added sheep dung, twigs, redried used leaves and the sweepings from the warehouse floors. “Smooch” was a frequent substitute ingredient; this is the forerunner of herbal tea. Extra nature’s little helpers included licorice, willow and sloe leaves. One of the main reasons English tea buying shifted from green to black seems to have been the widespread distrust of the sellers.

The most popular tea was bohea. It was all the scrap, broken leftover pieces, and twigs, dust and fannings. It was piled up and picked over for the best bits. The remainder was then compressed into bricks, the name by which tea became known. The term bohea fell from being generic for tea to meaning trash.

The Boston Tea Party acted on political grounds. They would have been fully justified as acting out of good taste; the tea was old and low grade. The sea journey from Asia averaged close to a year and it could take several years before the tea was sold. The East India Company had been stuck with seventeen millions of pounds of taxed tea in England – because of the smugglers offering a better deal. The colonies were a dumping ground for old, stale mixes of bohea and smaller amounts of congou, hyson and souchong.

Once the tea tax burden was lifted, tea improved and the Dutch lost their stranglehold. Its East India monopoly faded away through notorious incompetence, corruption and indolence. Wars with the English had gradually eroded its global bases.

An island named Run

One of the truly dreadful deals Holland made in the key peace treaty was to insist on retaining the tiny island in Indonesia called Run that had been richer than any gold mine, Silicon Valley IPO or movie deal.

Run was the only source of the very costly nutmeg and was remote, pirate-rich, dangerous in its currents and rocks. Holland and Britain had fought over it for decades, with the Dutch brutally massacring prisoners.

This was too good to give up, so the Dutch offered Britain its New Amsterdam colony, which was then renamed New York.

As the Dutch trade empire contracted, so did its domestic tea market. Individual firms continued to play a role in the emerging global industry but there is only one brand name.

Douwe Egwerts has been in business in Amsterdam since 1753. In 1937, the wife of the managing director had a brainwave; marketing the tea would be far more effective if it were branded as English. Hence, Pickwick tea, named for a book by her favorite author, Charles Dickens. Pickwick English Tea Blend bags are sold in several European countries and can be bought on Amazon.

Let’s see… English tea was almost all Dutch. Dutch tea sells only by being English. This bag of Indian chai is from Dubai. That British Blend is made by an Indian company that blends and packages it in Florida. There are a few perhaps surprising messages from this story that re relevant for your own choices of tea:

Don’t give a thought or pay a cent extra for the “English” tea hype. That includes Earl Grey. Tea has historically been driven by its supply chain and shipping and remains so. Dubai is the world’s center for tea re-exports, with its ports ideal for providers in Sri Lanka, China and Africa to transport bulk tea. The industry offers the facilities and tax breaks for tea brands to produce and distribute their products efficiently and cheaply. Labor costs make it economically compelling for one of the oldest and best known pedigree English elite firms to shift production to Poland.

Forget the label names. Good tea is all about the leaf: where it comes from, how it is processed, and the reliability and quality control in the supply chain. Many of the mass market packagers are the equivalent of the Dutch; they are in the business of shipping cheap tea and sometimes that means not so much adulteration as additives, low grade bohea-like dust, color enhancers, emulsifiers. They can put any name on it they choose. And do.

The more you know about a tea’s region of origin, how it’s harvested and processed, its estate, climate and pedigree, the better positioned you are to find value and pleasure in your teas. The more you buy from a supplier who handles the journey from bush to cup to ensure freshness and quality assurance, the less you will ever need to mutter “yuck – verschrikkelijk.”

Featured banner by Tasneem Amiruddin