I looked up at the lazily whirring fan, wondering why I was there. Then I remembered that it was because it was free, a free session at the Galle Literary Festival in Sri Lanka that was otherwise ticketed. I scanned the schedule to find a more appropriate discussion for me but the idea of stepping out into the brightening sun was deterrent enough. I stayed on.

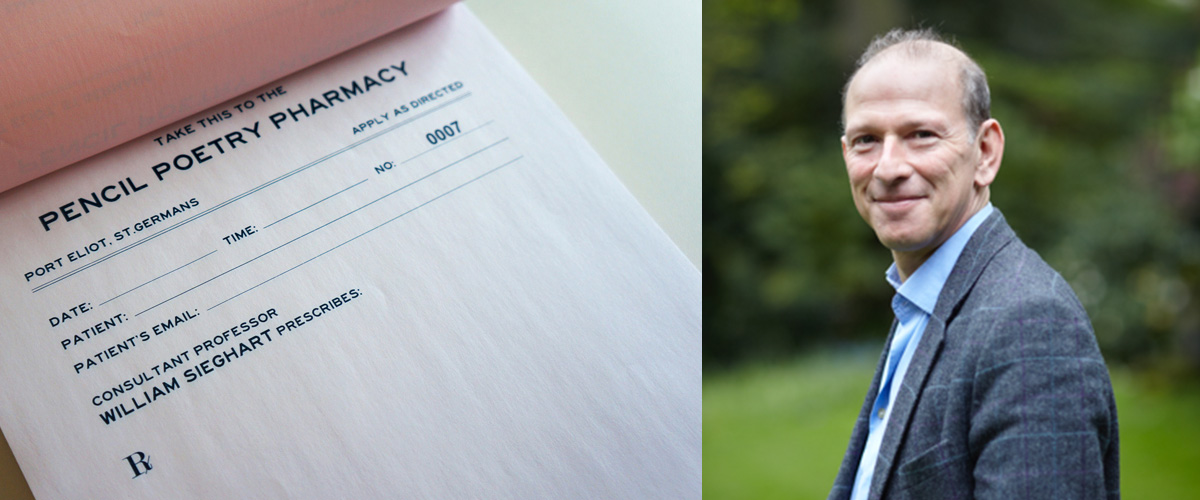

It was a one-man session to be led by William Sieghart of whom, to be honest, I had never heard of, probably because he is a poetry champion. Poetry is the section of a book fair or store I avoid. And the self help section, though the two could not be farther away from one another. Yet, here I was, at a talk where Sieghart, a poetry evangelist, and founder of the Forward Poetry Prize and National Poetry Day, would illustrate how poetry could cure our heart’s ailments. In the UK, where he is from, Sieghart holds “poetry pharmacies”, in which he hands out balm in the form of poetry; combinations of words that offer relief. In a world that seems perpetually overwrought and in search of therapy (book therapy, art therapy), poems seemed made for it. Though I might not get verse, I surely was interested in broken hearts.

My only brush with poetry had been in school. Even then, I remember, looking at single column poems in the annual school journal I had thought, “What a waste of space. This could have held so much more.” I didn’t detest it but poetry and I were, I thought, incompatible. At that time, I wanted structure, poetry gave me freedom. When I wanted characters, poetry gave me mankind. When I wanted stories, poetry gave me ideas. Poetry would probably have given me wings but I was content to be led.

But the moment Sieghart started speaking I knew I had made the right choice. His voice is one made for poetry – deep and gravelly with perfect cadence and diction. He could be reading out the alphabet and I would ask him for an encore. A voice you can fall asleep to. But no one did. It was a small, intimate gathering, probably of twenty people, half of whom had slipped off their shoes and were setting cross-legged. It was not a lecture, it had the comfort of a support group. People spoke of their deepest fears among strangers, of loneliness, of rootlessness, of feeling overwhelmed and hopeless for the world. As for me, I am terrified of public speaking. I cannot raise my hand even if my question was burning a hole in my heart. It was a morning of surprises. I raised my hand. And asked Sieghart if he had anything for a person who always felt small. And he did. ‘Come to the Edge’ by Christopher Logue:

Come to the edge.

We might fall.

Come to the edge.

It’s too high!

COME TO THE EDGE!

And they came,

And he pushed,

And they flew.

The next time I met Sieghart, it was at the Dutch House, a lovingly maintained colonial mansion built in 1712 that sits high on a hill overlooking the Galle Harbour. Owned by Geoffrey Dobbs, the founder of the fest, the house is surrounded by patches of tropical forest. A troop of monkeys swung its way through the trees. I had asked Sieghart for some time to discuss his “pharmacies” and he had asked me to join him at the house for a cup of tea. Though the tea never materialized, we did have a good chat.

[bctt tweet=”“I think it is perception and fear. Poetry has a poor brand.””]

I started by asking him why he thought people picked prose over poetry. He said, “I think it is perception and fear. Poetry has a poor brand. People think of it as a back-of-the-bookshop elite thing that’s probably not for them. And ironically they have quite a big love for poetry – some lines they have memorized as a child. But actually, poetry is everywhere – greeting cards in the UK, chanted on the football terraces, it is on radio commercials. It is all around us. But somehow or the other when you use the P-word, it intimidates. It intimidates the intermediaries, the librarians, teachers, people who work in bookshops. If those kinds of people are frightened of poetry, then people growing up and readers who go into bookshops will be frightened of them as well. They will head for the fiction.”

When Sieghart started promoting poetry, his challenge was to take poetry out of poetry corner. He published a poetry anthology called “Winning Words”. Like all authors, he went on a promotional run. It was at literary festival in Cornwall in the South of England, where a friend of his came up with the idea of a pharmacy. “She had designed a poetry prescription pad and had it printed. I thought I would just do it as a bit of a gimmick and see half a dozen people for 10 minutes each in a tent. But five and a half hours later the queue was still going around the tent. And I realized that my friend Jenny’s idea was rather remarkable,” said Sieghart. He has conducted about a 100 of these across the UK.

Unsurprisingly, most “patients” come to him with similar problems – loneliness, fear, anxiety, needing a kickstart in life, needing courage, end of a relationship, wanting a relationship, issues with your children, issues with your parents. “All the human things you would expect — the human condition,” he said. But still, at times someone comes along with a problem that is tough to solve with words. “It was most challenging when someone who was being stalked, came to me. The stalking story was just so awful and scary that I really felt that she needed a gun and not a poem,” said Seighart.

He admits that these pharmacies have tweaked the way he reads poetry now; at times looking for a pharmaceutical product in poems. “It’s partly about a problem shared, the feeling of complicity. We all know that our minds can be filled with some very troubling thoughts. And one conversation with a kind and wise friend can change everything. Maybe a poem can be that friend,” he said.

This feeling of complicity started early for Sieghart. The first poem he learnt was a Latin one. “When I was at school, I had won ten shillings as a prize for reading it out loud. It was about the ancient Greek story of Icarus. The idea of reading poetry aloud in my head became a habit. Particularly as I got older and I started to use it as a way to connecting to various feelings I had and started to find a complicity for my thoughts. The right poem can help me make sense of life,” he remembered.

As for me, I wanted him to recommend a poem for loneliness, an affliction I feel is inescapable in our modern lives.

Sieghart said, “Probably the most famous one for me is one by the Persian poet, Hafez who wrote 800 years ago and this is in translation. [bctt tweet=”‘I wish I could show you when you’re lonely or in darkness, the astonishing light of your own being.’”] Two very beautiful lines which I think for anyone who is feeling lonely and isolated, a rather lovely poetic balm. I would recommend them to commit this to memory or stick on their mirror, to have it with them always.

Photo courtesy: William Sieghart