Prachi Sibal catches up with poet-painter Tanya Mendonsa to talk about living in the Nilgiris.

Since I was a child, I’ve wanted to live on a tea estate. Growing up in Calcutta, my family often visited friends in Darjeeling who lived on tea estates, and I was enchanted by the life there. The rambling colonial bungalows on the tea estates, the leisurely tea times on vine-covered verandahs, the spreading lawns bordered with massed flower beds, the lazy pace of life remained a dream at the back of my mind.

I left India to work in France for 20 years. Once I returned to India, I moved to Bangalore to open a lending library. As it began to be over industrialized, I moved to Goa. When that became ruined by overdevelopment, finally, after fifteen years, on a “it’s now or never” impulse, I moved to the Nilgiris with my partner Antonio (an abstract painter) and my two beloved dogs.

During my early years back in India, I had often thought – and finally rejected – the idea of moving to the north. The mountains were too stark there; the distances from towns too great. A chance visit to the Nilgiris locked straight into my dream. I had never been there before, but it was as if it had always been waiting for me. The gently rolling hills, the dazzling, tapestried shades of green, the waterfalls and rivers and, above all, the stone houses nestling in the folds of the tea estates there enraptured me. It’s been over four years since we moved here, and I can’t see myself leaving.

We were lucky enough to find and buy a piece of land in the middle of one of the divisions of the Chamraj tea estate, equidistant from the little towns of Coonoor and Ooty, and the house we built overlooks over a valley where a river runs. I’ve always preferred a river to the sea, and seeing this river change over the seasons, moving from a time of drought to flood, watching the variations in the weather, has inspired a new direction in my work.

The main reason I wanted to live in the Nilgiris was the isolation of a tea estate; rather like a fairy kingdom shut off from the world. Above all, I had longed, after the hectic social life of Goa, for silence, only broken by the sound of birdsong or the wind. What was a revelation to me, coming from expanses of hard blue sky, were the skyscapes. With the constant changes in weather – from bright sunshine with fluffy cirrus to a mist that blotted out the entire landscape and invaded the house in just a quarter of an hour – came so many thoughts and ideas, crowding each other.

On arrival in the blue mountains we rented a stone cottage in a hollow at the Craigmore tea estate, which borders on the Allada Valley division of Chamraj. Almost a hundred years old, it had fireplaces and nooks and corners, every door opening onto the green of a garden that stepped down three levels.

When we moved to our own house at Chamraj – the laborious building of which deserves a novel to itself – the landscape changed dramatically. The views were spectacular, and our house looked out at an untouched Shola forest that bordered the river in the valley below. At almost any time, one could see herds of wild bison, sometimes as many as 30 or 40; mouse deer flipping their white scuts among the tea bushes; flocks of squirrels and, of course, the birds. At night, or in the early morning, if one was lucky, one saw black bears and panthers. The nearest house of one of the managers was two kilometres away. Apart from that, there are only the “lines”: the little stone houses of the tea pluckers. Alas, that is changing as I speak, because a lot of people have “discovered” the “untouched” Nilgiris!

There are many favorite things about living on a tea estate, being able to look out continually on green being the first. I love the constant changes of weather – when the mist blankets the house I feel cocooned in safety; when the sun blazes from an azure sky the whole landscape sparkles. I love watching the changing skies; I even love the rain – “Your English weather!” Antonio calls it, as if I’ve summoned it personally, for he hates continuous rain. Most of all, I love the isolation, the lack of constant houseguests (although that is a fact of life for the managers of the tea estates, and they seem to enjoy it thoroughly) and the way I can – within limits, of course – do anything I want when I want to do it. I force myself – or rather am forced by circumstances – to go “into town” once a week, but allow myself the treat of visiting the Nilgiris Library (founded in 1856) to borrow books or to go to lunch at the Ooty Club, stuck like a fly in amber around circa 1850 – drinking a pink gin in the “mixed bar“ one can almost hear the sounds of the hunt!

I have to admit here that I’m not one of those sturdy “pioneering” souls. I cannot mend a fuse, get up on a ladder, unblock a drain or do a million other practical things, including being able to drive. Being a “fixer” – or having help to fix is a prerequisite of living on a tea plantation, and that determines living alone or not. So it is with me, no matter how much I want or need to be alone. Unfortunately, one has to eat, and that means shopping, unless one lives on home-grown vegetables, which I am happy to do as long as I don’t have to grow them myself!

I’m not afraid of the “wild animals” but, as an animal lover, I respect them, which means I keep them at a safe distance, unlike our mountain mongrel Ninotchka, who is fearless and has learned to rue her bravery after being charged by a baby bear.

The temperature of my day is set by my early morning walks… I just amble around in different directions, often writing in my head; often stumbling or falling into a ditch as I watch the changes in the vegetation at my feet or look up at the moving skies! I generally “write” in the mornings. At other times of the day, as and when thoughts come to me – or, if I’m lucky, whole lines of poetry or prose – I scribble them in a large notebook. Too often these scarves of thought come at night: I’ve learned to force myself to get up and write them down, because I know they will have disappeared in the morning. Of course, if I have a deadline, I work steadily through the day, except for my siesta, as I’m a great sleeper!

After my morning walks, my favorite thing is picking the flowers in my garden and arranging them in jam jars; it is my morning puja. I generally write at the dining table, looking out over the valley, surrounded by jars of flowers, with especially beautiful wild ones in little specimen glasses. Whenever I get paid for any writing, I rush off to a nursery to buy more roses, which are my favorites. Most of my “best” roses are grown from cuttings of wild roses, which are thick stemmed with fierce thorns and beautifully parti-coloured: cream and apricot, scarlet striped with white, pink stippled with rose madder, yellow alternating with orange. The loveliest of them all is fuchsia splashed with peach, grows over my dog Joshua’s grave and has blooms the size of an open hand. I also love sitting with a book and a whiskey and watching the dusk fade into night – almost my best time of day.

Of course, I miss my good friends, who can’t visit as often as they might want to, given the tortuous journey involved to reach us, but the truth is that not only am I increasingly wedded to my solitude but I am increasingly disenchanted with domesticity. Left to myself, I would happily live on curd rice and cheese sandwiches, but could one expect loved ones to visit and subject them to the same fare?

A real problem is the vexed one of language. Despite having run a language school in Paris, I have a tin ear when it comes to learning a new one. I’ve managed to learn a few phrases of Tamil, but on the whole I’ve become quite proficient in mime, which seems to work adequately. “Show” rather than “Tell” says it all! As well, given the difficulty of getting help, I’ve learned to pare life down to the essentials. If the electrician can’t come for a week, one learns to love candle light; if the car breaks down, one simply doesn’t go out. In the end, one doesn’t miss a lot of things that one once thought were essential.

All the drama in our existence is provided by Antonio, who is a firecracker and lives in a constant state of drama, mostly self-created. Last year there had been a drought. When the river, as well as the municipal water supply, dried up, the wild bison were ranging far and wide in search of water. When it was already dark one evening, there was an immense bellowing from the water tank in the valley below. An enormous specimen, attracted by the scent of the water remaining at the bottom of the tank, had overbalanced and fallen into it. Antonio’s finest moment had arrived. The local Forestry Officer (who had planted 300 saplings for me) and I are great friends. I called him, and he arrived in fifteen minutes with twelve of his men. Alas, the bull had hurt himself badly when he fell. Despite all the efforts of the men to try to rope him up to safety, he was dead by the time he was brought up. All this took a good two hours, while Antonio rushed around with torches, cups of tea, not to mention shouting advice continuously. I stayed safely on the verandah above.

A happier incident took place this year, on Valentine’s day. It was the breeding season and one could hear the bison roaring to their prospective mates deep in the forests from early in the morning. Again at dusk, an overeager young chap pursuing his lady fell, by mistake, into the same water tank. Fortunately it was quite full, as it had been raining continuously for months and the young bull was swimming bravely in the water. The forestry men arrived immediately after our call, cut down huge logs of wood, lashed them together, and put down a ramp into the tank. They then managed to lasso the bison and help him up the ramp, at which point they cut the rope and scattered to a safe distance. The bison, none the worse for his ducking, shook himself, gave a happy roar and galloped up the hillside to tell his story to his love who, I’m sure, accepted his advances after he’d made such desperate efforts to win her!

I have to say that, if one wants to live in the Nilgiris outside of the towns, one has to have some creative occupation. It can be organic farming or simply creating a beautiful garden – they say if you place a seed on a rock here, it’ll grow! – or doing woodwork; it’s not necessary to be a great painter or writer or musician. One simply needs a creative spark to enjoy living in isolation and to profit from it.

Otherwise it can be a monotonous and boring life – I see many people simply treading a daily round of lunch, tea and dinner parties interspersed by visits to the club. Happily, this sort of existence requires a lot of money, which is something I shall never have, so I’m safe forever!

I wrote my second book of poems, All The Answer I Shall Ever Get in the space of a little over a year. While I had been writing that book, I became increasingly fascinated by the idea of solitude. This was reinforced by my walks, where I passed – or saw, in the distance – abandoned little stone houses nestled in a copse of trees or set against the flank of a hill, mostly with a stream beside them. Wild marigolds grow there; poinsettia; sunflowers and the nameless little flowering grasses and weeds beneath peach or cherry trees, all haunted by birdsong. I fantasized about living in one of those houses (I could, now that my Joshua was gone) and all the things I would gradually discover. Of course, “my“ house would have to be far more isolated, away from the tea pluckers and other distractions.

So I began to jot down ideas and verses as the months went by. Once my second book of poetry was finished, I came back to this idea, and worked out the thread of a story about a wanderer who discovered a new landscape one day. It is to be a fable for our times in short verses, called “The Fisher of Perch”.

Well, I shan’t tell the end of the “story”: I shall only say that, in the end, he realises that what he is really fishing for, metaphorically, is contentment and peace.

Walking one morning, I found myself in a space that was unfamiliar:

for once, I did not know where I was going.

The mist was thick and comfortable, like wearing a new coat.

When I put my arm out, I touched a vine and pulled it toward me.

It was supple but tough, with little leaves like lilypads.

Among the lilypads walked small pink flowers, with open mouths

poking out furry, scarlet tongues…

From “The Fisher of Perch” by Tanya Mendonsa, to be published in 2016

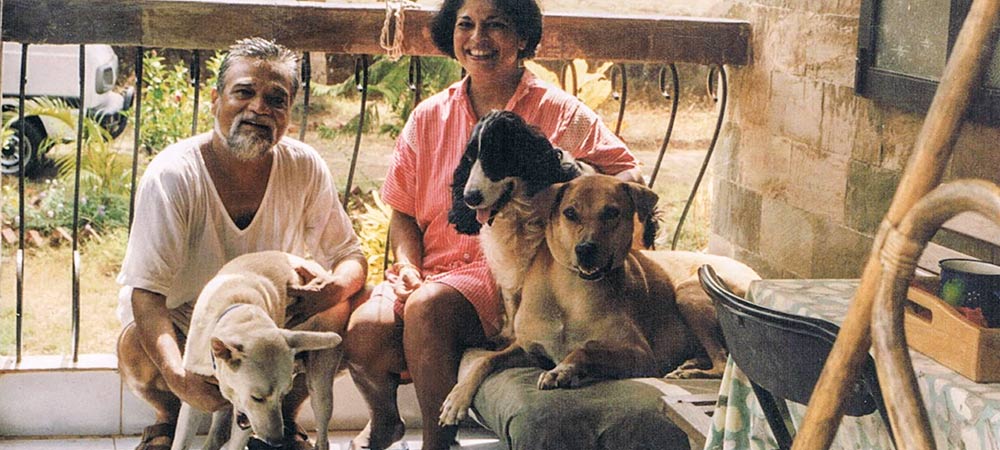

Featured photograph of Tanya Mendonsa with her partner Antonio and their beloved dogs.

6 Comments

Reading Tanya’s story has started me yearning for my hills again (thank you for such a lovely account of the “lonely life”)!

I grew up in an isolated tea estate in the Nilgiris (and can relate to all of what Tanya has said). Two generations of my family have been planters; my folks are still there. I would have loved nothing more than to live there all my life and to walk and look at the greens and blues day in and day out just as I did throughout my childhood. Circumstances have put me in the maddening rush of the city however. I hope the time to return to my beloved Nilgiri hills is not too far off!

Tanya’s brilliant writing is enough to make you pack your rucksack immediately! If only we could all shed the pressures of this chaotic, noisy existence and follow their example, the world would be a better place. Having an appreciation of the natural world brings more contentment than any material gains can ever do. I hope you escape to those hills again soon as through Tanya’s writing I have gained an image of a part of India that looks like Paradise.

I still dream of the days I spent with Tanya & Antonio on their wonderful piece of paradise. Naz & me will definitely return back , even if it means disrupting their ‘Solitude’ for a few days.

Looks ver similar to wailua Kauai Hawaii. Green, ever growing although no large animals to fall in water tanks. The slower quiter pace of life is a blessing for some of us. Wonderful relaxing story, I read out loud to my wife over afternoon tea. Thank you.

That was simply delightful.We would love to visit you in Coonoor even though it would mean(to quote Ricardo) disrupting your solitude!

Loads of love to you all.

I enjoyed reading about your life on a tea estate. My grandparents lived at Sans Souci near Coonoor for many years and I was at school in Coonoor. I have very fond memories of this lovely part of India.