Tea has had a pervasive impact on almost all areas of society for almost four hundred years in the West and somewhere between two and three millennia in Asia. It has been a consequential and even pivotal factor in war, nutrition, colonization, agriculture, health, technology and fine arts. But the marketing version is boringly simplistic and largely incorrect: Tea began in China, was first imported by England that turned the cuppa and high tea into a social revolution and gave the world tea bags and Earl Grey.

Nonsense. England was a very late arrival to tea, around fifty years after the Portuguese and Dutch. The main impacts of tea were on working class poverty and nutrition. Britain was the last tea drinking nation to give in to the tea bag. Earl Grey had nothing to do with his tea, which was first mentioned in any document in 1929, almost exactly a century after what is now claimed. The Earl ended slavery in the British Empire, had one of the more lurid affairs of the century even by the concupiscent standards of the aristocracy, and became a strong anti-Catholic campaigner. But he is innocent of that perfumed dust in a bag.

The true history is much more dynamic and intriguing. Here, for instance, is a sketch of its evolution in just one country. Can you guess which one it is?

The country originated as a colony of a large empire with its major city a pawn exchanged with another major power before its fragmented regions combined in a prolonged war to gain its freedom. It had the highest per capita tea consumption in the world, with its small population of around two million drinking more tea than the total for Britain’s ten million, an average of five cups per adult and child a day.

Its leader was a tea lover and personally managed the selection of the tea bought for his household, with his own breakfast routine three cups. He was noted for the money he spent on it and his excellent taste in both tea, porcelain and silver teaware and elegant accessories. His sort of friendly rival for leadership was the richest man in the country, who had built his fortune on tea smuggling. A pivotal figure in the rebellion was a noted silversmith famous for his tea ware. The best-known intellectual leader was a very sophisticated (and somewhat profligate) tea lover.

Its leader was a tea lover and personally managed the selection of the tea bought for his household, with his own breakfast routine three cups. He was noted for the money he spent on it and his excellent taste in both tea, porcelain and silver teaware and elegant accessories. His sort of friendly rival for leadership was the richest man in the country, who had built his fortune on tea smuggling. A pivotal figure in the rebellion was a noted silversmith famous for his tea ware. The best-known intellectual leader was a very sophisticated (and somewhat profligate) tea lover.

The new country soon became a major player in the tea trade, bypassing the reliance of other nations on China, that rigorously enforced its monopoly and many secrets of growing. It made a smaller Asian country an offer it could not refuse, the earliest example of gunboat diplomacy as its fleet anchored in the main harbor. It used this lever to open up entirely new trade routes, exploiting first its large bulk cargo carriers and then its superb ships that were the fastest in the world and dramatically reduced transport times across the major oceans.

Within a few decades over half its tea imports came from this new source of supply, which reshaped the entire tea production in response. Its tea drinkers disliked stems in their teas and the providers built on a new processing method that changed how the harvested leaf was treated.

The country pioneered many developments in tea production and marketing. It was the first to add alcohol to tea and launched the single largest technological shift in the industry that expanded the market for tea and transformed the global supply picture. Tea was the core for just about every innovation over 150 years in its grocery retailing, including mail order, convenience stores and self-service supermarkets, driven by a small chain of tea and coffee ships in the major city. This became the largest retailer in the world, far bigger even than Walmart, adjusted for inflation. Its name was the Great Tea company.

It was an early pioneer in efforts to grow tea, starting in 1772, a few years after the Dutch in Java. Both initiatives preceded the British creation of tea growing in India and were failures. The country continued to create small plantations with minimal success. However, today it is producing some outstanding white teas.

So, that’s the history. Which country do you think this is?

The USA, of course.

The colony: The core of what became the United States was the Dutch New Amsterdam island of 25,000. (Boston’s population was 17,000 and London’s 1.2 million.) That became Manhattan. The Dutch were the pioneers of the tea trade, the first to import it in volume, establish a colonial center (Java) and attempt to cultivate it. Holland swapped New Amsterdam in the peace deal with Britain that ended fifty years of naval warfare for the small Indonesian island of Run, which had a monopoly on the world’s most expensive commodity: nutmeg. History ranks this exchange as somewhat one-sided in its outcome. It meant though that what became the United States of America began as the largest tea culture outside Asia.

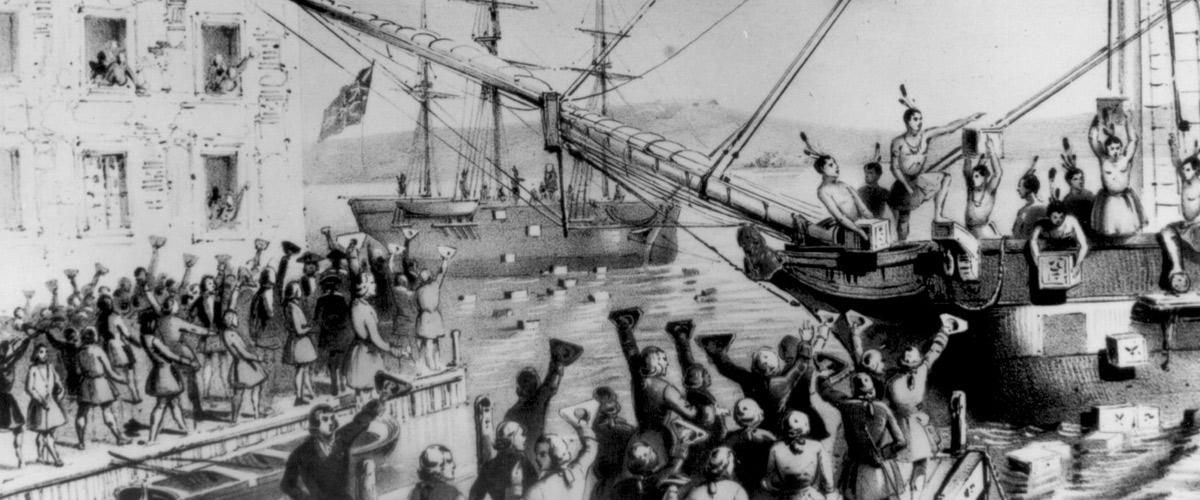

Tea was of course the trigger for the Revolution. The Boston Tea Party was just the last and biggest protest against the efforts of the massive East India company, the British trade monopoly, to use tax and customs regulations to dump its growing inventory on the colonists who consumed a million pounds of tea a year, three-quarters of it informally imported – smuggled – by Dutch ships. South Carolina and Maine preceded the Boston protests. (By the way, the inventory of tea dumped in Boston Harbor was stale, mediocre and less than pristine. It deserved its fate for reasons of taste, not just tax.)

The leaders of the tea-triggered rebellion were tea drinkers. George Washington loved tea. It appears even in his military orders and his guests have left anecdotes about tea at Mount Vernon. John Hancock was the smuggler, in collaboration with the Dutch, He was very good at it and is estimated to own a full one percent of all the wealth in the 13 colonies. He was just once formally charged with smuggling and got off, thanks largely to his eccentric but outstanding lawyer, one John Adams, who became the second President.

The intellectual, Thomas Jefferson, knew his teas well and his letters are very specific about what he wanted agents to buy for him. The silversmith was Paul Revere, whose famous ride to alert the colonialist to the arrival of British troops at Concord, thirty miles from Boston, was just one of his many contributions to the Revolution. He was a good man, an extraordinary inventor and the recognized leader in both design and technology in making glorious tea sets.

After independence, the United States joined the other naval powers in trading with China, including for tea. In 1853, it changed the international seascape. Commander Perry’s fleet of Black Ships intruded on the isolated Japan bringing a suggestion that it might be timely for this completely closed nation to open things up a bit. The military regime collapsed and the emperor was restored. British and Russian ships followed and the treaty of 1858 opened up the major ports for trade.

Britain had moved from dependence on China for its green teas to sourcing black teas from its Indian and Ceylon plantations, The US took the opportunity of Japanese tea growing, which was substantial, to build a massive independent supply chain. A young woman, Oura Kei, by herself generated interest in the unfamiliar new and unique style of Japanese tea, called sencha. Her samples led to an English trader placing an order for around 12 tons that O-Kei-Chan amassed from the small growers across the country over a three-year period. She created and built up the Japanese export market and was a brilliant entrepreneur and manager. (Japan did not and does not rank high on any list of countries in support of women’s rights and respect.)

Most of the new tea supply went to the US. In 1870 a quarter of its imports were from Japan and fully half in 1880. They declined after that. Sencha was not popular domestically and was made only for the American market, whose consumers liked its stem-free, small and bright leaf. Growers gave nature a nudge. They added Chinese secret extras, most notably graphite and cobalt blue. Yes, they are indeed poisonous but made the green even brighter.

To meet the volume of demand, processing factories short-circuited the drying and heating steps that make sencha, now the mainstream in Japanese production and consumption, so special. Congress passed the world’s first anti-faking laws, the American taste moved on to Indian black teas and finally World War II ended the Japan-USA trade link. Japanese teas eroded from constituting the US market to being invisible in it and only now reemerging as a specialty sector.

The distinctive element of the US tea business was shipping. The European vessels that made the six-month transit across the Pacific were not designed for cargo. The East India’s giant Indiamen lumbered at slow speeds and were heavily armed. They needed lighter ships to travel with them to deal with the pirates that lurked on every horizon.

When Perry anchored in Yokohama Bay, the US had the world’s largest fleet of flat-bottomed, weather-endurant boats with their own coal-fired on board engines, unlike the sailing ships. These were becoming rapidly obsolete. These were the whaling boats of the Pacific. They were ideal for carrying tea instead of whale oil. One real-world Pacific rogue whale was immortalized in a novel as Moby Dick. You can see the last whaling station that was its reputed haunt on the coast of Chile.

The need to hunt whales had ended when the streets of Philadelphia were lit up by the newly discovered natural gas. The whalers were ideal for mass cargo handling, especially tea which posed many storage problems on the two- and three-decker Indiamen. Damp was the most obvious, but so too was balancing the load to keep the ship and its cargo stable in the storms that could turn a tranquil flat ocean into a hellish turmoil in just minutes. The rapid growth of the demand in Europe for China porcelain was fueled by its being added to tea shipments as ballast.

The East India company’s monopoly was ended in the 1850s (at its peak, it owned a large army and navy, governed India, created the illegal opium trade, and was infamous for corruption, greed and bribery. Earl Grey, interestingly, led the failed impeachment of its CEO, also Governor-General of India.

With the monopoly dead, speed became the trade differentiator. US ships led the surge of innovation, starting with the Baltimore clippers, so named probably because they clipped the waves. These were very sleek and fast. They began in the shipyards of Baltimore, Maryland, during the Revolution and were designed to outrun the British sea blockage. They were narrow and carried a huge set of sails. In the 1890s, alas, they became the equivalent of the cigarette-boats of cocaine smugglers and used to get Indian opium into China. They were ideal for carrying perishable high value, small cargo items. Beyond “alas”, that included not just tea but slaves.

The clippers got bigger and the term tea clipper a commonplace. The Great Tea Race of 1866 was the epitome of the tea and speed combination. Rather like the premium paid for the first Beaujolais nouveau wine, the earliest tea of the season delivered to London from Shanghai commanded a price double the rest. All the records for speed, including a circumnavigation of the globe in just over four months belonged to the American tea clipper, Lightning, but the race was won by its notably slower British rival Ariel, with Lightning abstaining. It was one of the occasional informal challenges among the clippers. Five ships loaded five million pounds of tea in China and left on the same day. Ariel won by twenty minutes after sailing 14,000 miles in 99 days. It carried 36 sails.

America has tended to view tea as English, traditional and upper class. But many of the innovations in tea came from the US. It was the first to add booze. The earliest recipe for non-alcohol loaded iced tea appeared in 1876, but as early as colonial times, published ones contained over 20% alcohol. Regent’s Punch was green tea plus arack rum, citrus juice, champagne and brandy. A typical Kentucky recipe, in 1839, called for making a brew of strong tea, loading it with 2-3 full cups of sugar plus a pint of heavy cream and then stirring in a full bottle of claret or champagne.

Iced tea became respectable and teetotal when it took off at the famous 1904 St. Louis World Fair. The intense summer heat led fairgoers to ignore the hot drinks or add ice cubes to them. But the American contribution to what now constitutes 80% of the tea-based beverage market in the US, continued along a decidedly non-herbal path with the invention of Long Island iced tea in 1972. It’s ingredients included tequila, vodka, triple sec, rum and gin. Most of the variants of this iced tea don’t bother with the tea.

Finally in this historical precis, the United States was the direct and sole creator of the single most far-reaching technology innovation in the entire history of tea. The very first patent for a tea leaf holder was granted to two sisters in Milwaukee and the first commercial use of silk pouches for tea samples was launched by a New York tea trader. Thus came the tea bag to the cup, transforming and for many deforming tea forever.

Yes, the tea bag is American. The British disdained it, In the late 1960s, tea bags amounted to under 3% of the market. Your author came to the US in 1967 and had never seen tea in a bag or heard of Earl Grey. By 2007, the force of convenience and mass marketing had triumphed and 96% of tea in the UK was bagged. Tea drinking has dropped by 40% over the past three decades. This reflects competition from coffee and the declining quality of the cheap tea sold as a loss leader in most supermarket chains.

The US isn’t generally thought of as a tea nation. It suffers from too many mass market low end iced teas, herbal brews, no-name bags, medicinally-excused green tea of grimace-evoking vegetation, and restaurant-enhanced water. But it has the fastest-growing market for fine teas, with far more specialty stores than you’ll find in most regions of the UK and a wealth of online suppliers plus access to more and more Indian and Chinese sellers. By far the best packaged Earl Grey comes from a US company. It is in a class by itself. The best blends of standard teas look as if they are English, from the names and images but the firm is a relatively new one, a Connecticut start-up.

You can find just about any of the estimated 3,000 teas on the market. There is no reason whatever in the US to drink poor tea. The main barriers to growth are lack of buyer knowledge, especially of Darjeelings and the other outstanding teas of India and Nepal. Distribution of Japanese teas is weak.

Meanwhile, there is a growing development of the USA as – at last – a tea producer. White teas are the very peak of the craft. They are represented by Fujian’s Silver Needles, Sri Lanka’s Adam’s Peak and Silver Tips, and Darjeeling’s Castleton Moonlight that is fairly widely rated the best tea in the world. The US initiatives in the 18-19th century to grow teas fizzled out, but today the rich alluvial soil and slopes of Hawaii are producing distinctive high quality whites. They are overpriced and overhyped but it is not implausible that Hawaii Mountain White may be a premium tea in coming years

And while British rock singers wax lyrical about their English paint stripper teas of childhood, the inestimable Lady Gaga is seen as “the global face of tea” by advertisers and is noted for traveling everywhere with her purple and gold cup and for her lyric “It’s been oolong since I had a sip, and I get this feeling, I need a green detox, the truth will be the winner tonight.” May be she could do a voice over to accompany America’s Frank Sinatra’s voice in the classic universal tea song, from the American 1925 musical No, No Nanette: Tea for Two.