The demand for teas labelled as “white” is growing fast. This has always been a Showcase special: scarce, exquisite and displaying the best of the craft. The most outstanding came from Fujian Province in China and from Sri Lanka, whose Adams Peak is one of the highest rated teas of any type.

Supply is expanding. There are now excellent white Darjeelings, good varieties from other China provinces, and some fine ones from Vietnam, Malawi, the Nilgiris, Nepal and Kenya and even Hawaii. These teas are worthy of inclusion in the showcase. Some are more the equivalent of “home made style”, not quite the real thing but offering its main features. They include many lightly flavored teas that are a little greenish and lack some of the delicacy of the pure whites, though adding to their floral characteristics.

The simple answer to the question “What is white tea?” is that it’s a variant of green teas but minimally processed without any heating or rolling, so that they remain closest to their natural state. This retains the freshness and richness of the nutrients.

But in many ways, there’s no such thing as white tea. It name carries no legal weight or agreed on industry definition. It is distinguished less by what it is but by how it is made and why this differs from green tea production. This difference is analogous to that between “champagne” as a type of drink and the “methode champenoise”, which is the traditional one of four main ways of making sparkling wines. “Champagne” on a label doesn’t tell you much about the nature or quality of the drink; it’s the method that differentiates it.

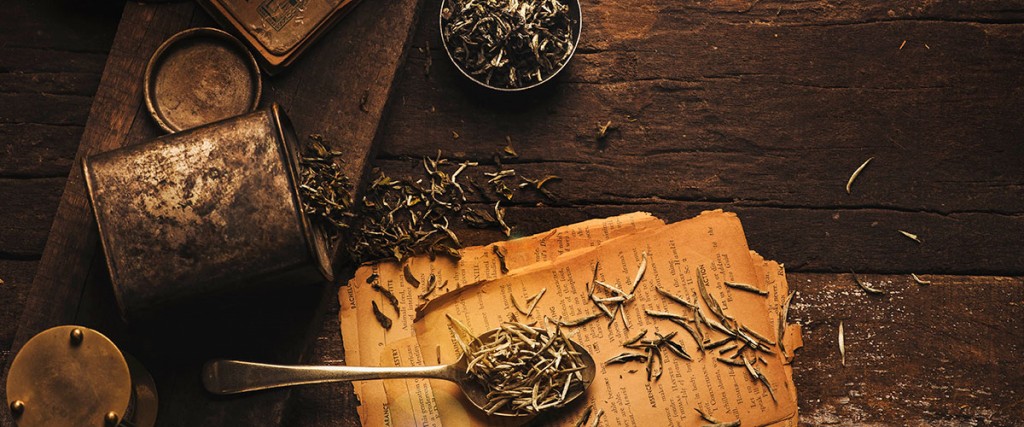

Showcase white teas come from what might be termed the “methode Fujian” of “minimalist precision.” It’s a way of “making” tea based on just let it be: Harvest the very best buds during the shortest period, and do as little to it as possible.

The plucking shows the minimalism and points to its cost. It lasts for just a single week or two in the spring, less than days before the buds unfold into a leaf; they are packed with nutrients built up during the winter. Harvesting stops if there is any rain, dew or frost. Only buds that have a full shape and long length are selected.

The main variety of bush is unique for the downy white hairs on the buds that evolved to protect against bugs. The plants provide an extra jolt of glucose that makes them sweeter than maturing leaves. They also add a boost of extra caffeine and the antioxidants that are believed to give tea medical powers of prevention and cure.

The minimalism continues. Nothing is done to the leaf beyond letting it wither in the air. The bushes are shaded a few weeks before harvesting to prevent the sun from stimulating the chlorophyll that greens the leaf. The tea is not allowed to oxidize – in theory, though practice varies. It simply dries. It is meticulously inspected to ensure that the final leaf is uniform in size and shape and unblemished.

There’s some fine-tuning in this traditional process, which produces the Silver Needle white tea that is a peak of the Artisan craft, with distinctive characteristics of wide appeal. It is surprisingly full while also delicate, so that its flavors expand in your mouth. It is subtle and smooth with a hint of sweetness and no astringency. The flavor is floral, whereas green teas tend to be vegetal, with a grassy aroma.

It is robust, too, and more tolerant of temperature and time in brewing than greens. Its flavors are strong enough for you to just let them unfold but light enough for any one of them to become dominant. Some people do find it too watery. It doesn’t demand an expert palate but more a sense of the palette of tea tastes built from experience.

Silver Needle (Yin Zhen) has pride of place in the showcase. Alongside are Eyebrow (Shou Mei), and White Peony (Bai Mu Dan). They ease away from minimalism. White Peony adds the two leaves below the bud, for instance, Shou Mei is a little stronger than Silver Needle. There are variants in the bush itself. Some of the withering adds a step that bake-dries, but does not heat, the buds to remove all the moisture. Buds that are not select enough for Silver Needle may be used separately. Some white teas are oxidized as much as lighter green teas.

These variations provide a rich range of choices but the core of the method remains the same for Showcase and Home Made Style: no processing, only withering. White tea is relatively expensive but not as much as its careful selection and low yields might suggest. Silver Needle starts at around 50 cents a cup. White Peony can cost less than half that; it has a wide range of grades. Ceylon Adams Peak is way up on the luxury scale: $2 a cup. The elite Darjeeling growers are towards the high end of the price range; they add an extra mellowness and a hint of sweetness unique to their terrain.

Or you can pay 40 cents for a white tea bag. You can but really shouldn’t. There’s a third “type” of white tea, which is mainly overpriced and often awful. Call this “Eat Your Spinach.” When a child complains that “But I don’t like spinach”, back comes “It’s good for you.” Much of the mass market demand for white tea is driven entirely by “it’s healthy for you.” It’s a follow-on to the green tea medicinal surge – the claims that it is a magic drug equivalent for preventing and curing most diseases and for losing weight.

The key factor here is anti-oxidants, compounds manufactured by the body that are believed to attack the free radical molecules that damage cells and impede DNA. White tea has the highest proportion of such polyphenols, around three times that of green tea.

The marketing opportunity is obvious. If polyphenols are a key to daily health and since white teas have so many of them then it makes sense to adopt them as your everyday drink. The “if” gets turned into “because” and “makes sense” to “is essential.”

Added to high anti-oxidants as health aid claim is low caffeine, where green teas are incorrectly assumed to be lower than other black teas. (Soil, harvesting and brewing have far more impact.) White teas must therefore be even lower. This is the assertion that pops up on so many Web sites. They are not at all low in caffeine. Some are twice as high as the average black tea. (Eat your spinach.)

Most of the teabag whites also stress that they come from Fujian, that the tea is minimally processed and made from buds, etc. It doesn’t say that what they are packaging are the rejects from this, the stuff discarded as unusable in the equivalent of the method champenoise. It is dust and fannings and even powder. These lack the flavor and freshness that mark good whites. Even the major brands state that “our” white tea is an instance of one of the most outstanding of all the teas in the world though it’s made of dreck. Without the health pull, it’s just a low end bag priced at high end whole leaf.

There are so many good choices beyond these. It’s worth starting with an affordable Silver Needle and trying out a White Peony or two. Whether as an occasional, frequent or staple part of your tea stock, white tea is a joy.

1 Comment

Dear Peter,

I’m in love with teas and it’s my job. Your fabulous articles have given me the opportunity to learn more and more about this millennial culture.

Thank you so much for this!